Weimarer Republik:

Make Way for the Automobile!

The German capital found itself in a difficult political and economic situation during the Weimar Republic. Greater Berlin was founded in 1920 accompanied by ambitious plans, and yet the new administrative structure was unable to deliver them. Although at the time there were only few cars on the streets of Berlin, there were radical visions for a future as a car friendly city. The designs of independent architects such as Ludwig Hilberseimer and Ludwig Scheurer are testament to these ideas. In the late 1920s, the city of Berlin, with the help of two city councillors – Martin Wagner and Ernst Reuter – also drew up expansive plans to accommodate a large influx of traffic. The plans peaked in the spring of 1930 when a “redevelopment plan” for the southern part of the historic city centre was drawn up. It presented a novel and radical proposal for the modernisation of central Berlin. By breaking up existing roads to create new ones, it intended to allow cars to transit from east to west across the old centre with ease. However the global economic crisis took a heavy toll, and the plans were only partially realised at Alexanderplatz.

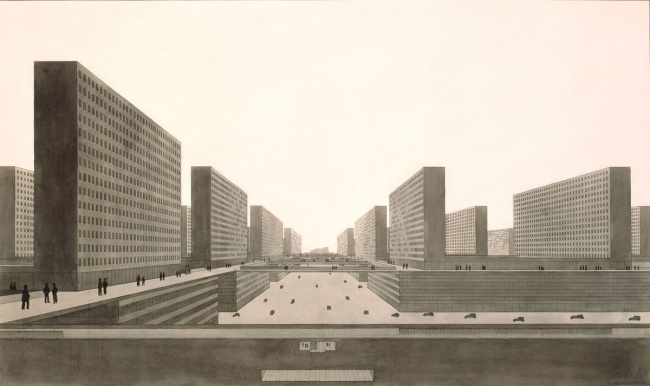

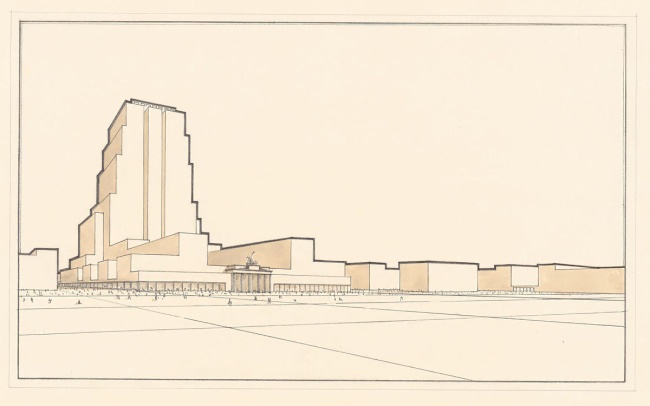

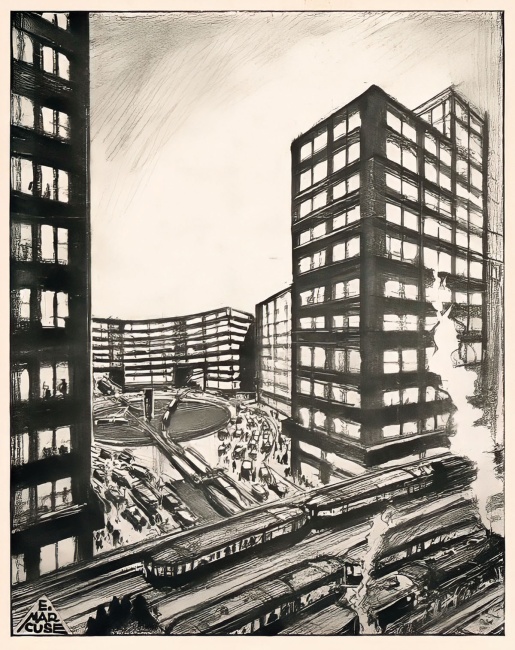

View from north to south of the “high rise city” by Ludwig Hilberseimer, 1924

Ludwig Hilberseimer (1885–1967), professor of urban planning at the Bauhaus in Dessau from 1929 to 1933, rivalled Le Corbusier for the most radical concepts in urban planning in the 1920s. His “high rise city” design oscillated between urban planning and schematism. All local transport was to be moved underground and all middle-aged residents were to live in serviced apartments in the long, towering blocks. However, confined to the sixth floor, residents would have to negotiate long routes by foot whilst cars could navigate freely around the 30-car-wide lanes.

The Heart of the Historic City Centre: Spittelmarkt to Alexanderplatz

The 1920s plans for the redevelopment of the city centre were radical, car-oriented and ultimately destructive to historic buildings. Alexanderplatz was designed first, followed by the southern part of the historic city centre including Molkenmarkt and Mühlendamm. The development at Alexanderplatz was only partially completed with the Berolinahaus and Alexanderhaus, designed by Peter Behrens, due to political and economic constraints. From then on, municipal city planners focussed exclusively on traffic flow and no longer on the development of streets and squares.

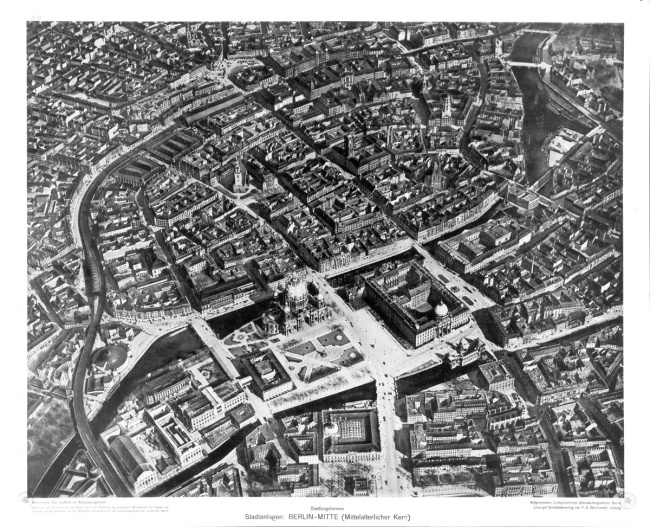

Iconic oblique aerial view of Berlin’s historic city centre from the west, 1928

The most common pre-War aerial photograph of Berlin is based on the school chart “Forms of Settlement. The City and its Medieval Town Centre”. This panel showed schoolchildren the beauty of the Berlin old town with its gently curving streets that still formed the centre of the growing metropolis.

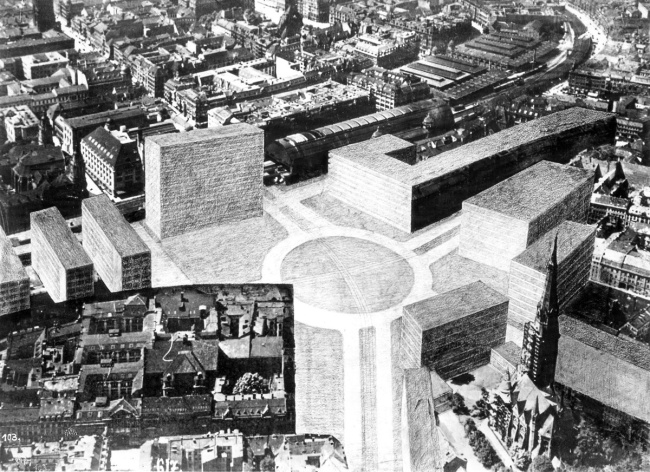

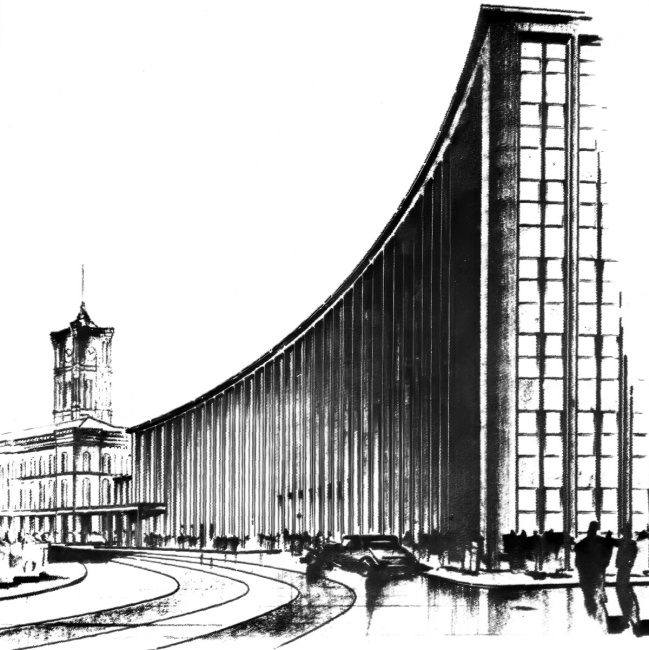

Mies van der Rohe’s entry for the Alexanderplatz urban design competition, 1928

The architect imagined huge glass office panes centred on a wide roundabout. In the foreground, a densely built up area around the teachers’ association building appears totally alien, disconnected from the new Alexanderplatz.

Alexanderplatz – a big building site, November 1930

The underground line E (now the U5) was laid underneath Alexanderplatz between 1928 and 1930 using exposed construction methods. The two gatehouses designed by Peter Behrens were built between 1929 and 1932. This view looks northwards from Dircksenstrasse to the station forecourt with the building site of the Berolinahaus and the Tietz department store in the background.

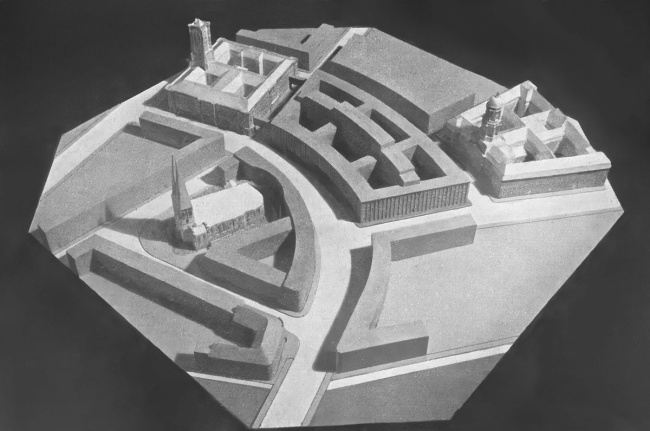

Model of a new main road through the old town, 1931

The traffic planners created a large quarter-circle curve from Mühlendamm at the bottom of the picture to the town hall. This new main street was designed to subordinate a number of buildings: the Molkenmarkt, Palais Schwerin, the Nikolai quarter and a colossal future third town hall.

Illustrative sketch of two blocks housing the Third Town Hall on Molkenmarkt, 1931

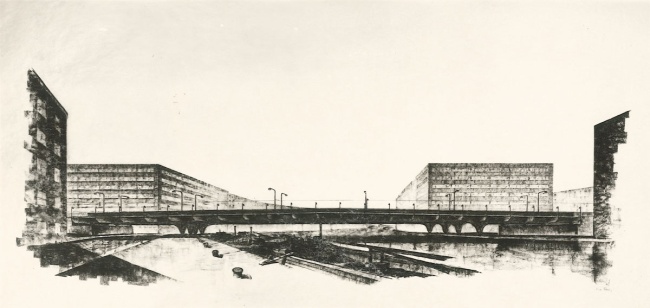

Diagram of a new multi-way reinforced concrete bridge at Mühlendamm, 1931

The Ephraim Palace – “the most beautiful corner of Berlin” on the right-hand side of the bridge was demolished to accommodate this new construction. The city council’s transport planners had designed a proposal that would allow the palace to remain in situ, however politicians were petitioned not to approve these plans.

Bird’s-eye view of the opening made through the Grunerstrasse–Jägerstrasse with the Nikolai Church in the background, June 1931

In the interest of accommodating more cars, city planners relegated the Nikolaikirche church to the centre of a traffic island. This bird‘s eye view of Jüdenstrasse shows the schematic layout of the Third Town Hall with its comb-like structure.

The Heart of the City: Leipziger Strasse and Potsdamer Platz

Growing congestion in the old town was blamed on its narrow, winding streets and the layout of the former fortress bastions. And yet, in Friedrichstadt, the very heart of the old town, the streets were generous and completely straight. However, urban planners had already sealed its fate, and large tunnels and bypasses were developed as well as structures to separate types of traffic. Even BVG board member Paul Wittig conceded in 1931: “There has been a traffic reduction in Berlin [...] to such an extent that an emptiness hangs over the formerly crowded streets.”

View from Leipziger Platz into the Leipziger Strasse shopping mile, around 1920

Tram and bus transport was the main mode of transport in 1920, but soon the number of cars had begun to grow rapidly. The volume would far exceed the pre-First World War figures, eclipsing the local transport network. In 1921 there were 12,000 cars registered in Berlin, while in 1930 there were over 90,000.

Bypass of Leipziger Strasse, by master builder Friedrich Brömstrup, 1931

When outlining his plans for the “reorganisation of Berlin inner city traffic”, Brömstrup wrote: “Berlin [...] is approaching a watershed moment for urban planning.” The city can no longer support its traffic. “Road widenings and cut-throughs” are essential and the elevated bypass is inevitable.

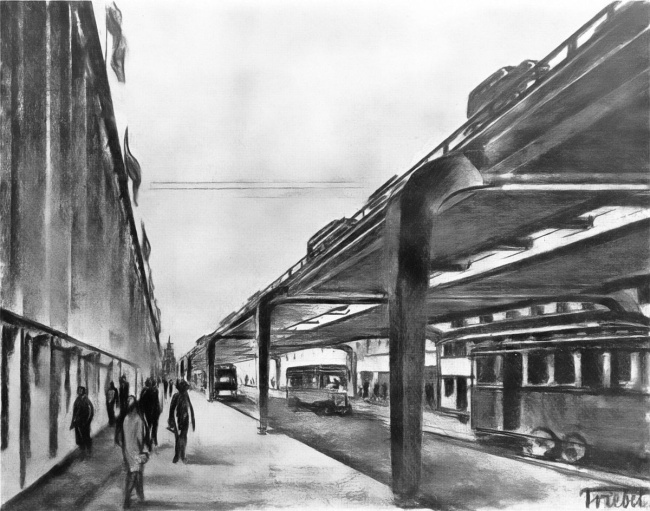

Design for a “main junction with an overpass” by master builder Friedrich Brömstrup, 1931

In 1931 Brömstrup set out a proposal for an extensive “elevated motorway network” for Berlin. This included car-friendly inner-city junctions on several levels. The pedestrians in the foreground are on a raised walkway.

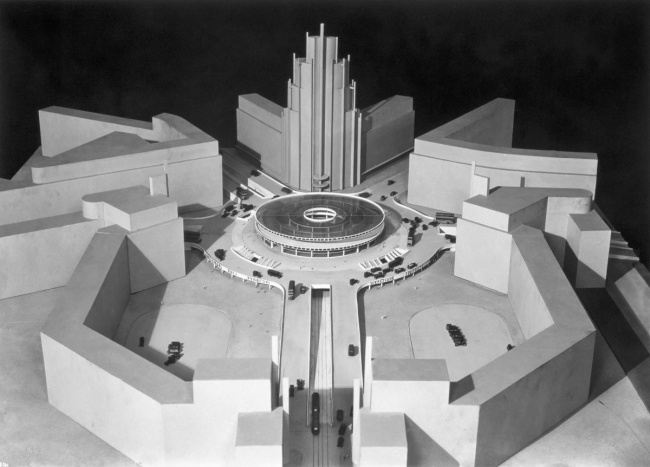

Martin Wagner: Model of Potsdamer Platz, 1928/29

View from Leipziger Strasse onto Potsdamer Platz: the main traffic passes through a tunnel whilst turning traffic is routed through an elevated roundabout. Pedestrians navigate at ground level and through an inner ring road of the junction. Leipziger Platz in the foreground was divided into two permanently separate areas.

Policemen being trained at a replica of Potsdamer Platz, around 1934

As traffic increased, so did accidents and casualties. To counter this, the New Traffic Regulations of January 1929 restricted pedestrian traffic by means of roadside barriers and designated crosswalks. The photographer of this scene, Martin Dzubas, worked in the traffic and technology department of the Berlin police until 1933.

Potsdamer Platz with bus, tram, and the Verkehrsturm traffic tower, April 1927

The Verkehrsturm tower, Germany’s first traffic light, has signalled traffic around the five intersecting streets of Potsdamer Tor since December 1924. Despite the rapid increase in car traffic in the 1920s, buses and trams still formed the backbone of urban transport in 1927.

The “Unter den Linden” Competition, 1925

This 1925 sensational competition to redesign Unter den Linden – organised by Wasmuth’s monthly architecture journal and the Städtebau magazine – is a prime example of the arrogance of some architects to design a new Berlin at the expense of the old. Not a single building along the via triumphalis of the former Prussian rulers was to be preserved, bar a few outliers from the 18th century. This competition is comparable to the 1910 Greater Berlin competition both in terms of design, and the participants’ hostile attitude towards existing buildings.

Competition entry by Erich Karweik: tower block overlooking Pariser Platz, 1925

Erich Karweik, who was unable to complete his architecture training due to the First World War, worked in Erich Mendelsohn’s firm from 1922. His competition entry featured an enormous tower block overlooking Pariser Platz. Unter den Linden was to be completely rebuilt and uniformly developed on both sides.

Competition entry by Ludwig Scheurer: motorway and tower blocks, 1925

Ludwig Scheurer, later a city planning officer in Essen and presumably involved in the construction of the Reichsautobahnen (Reich motorways) under Fritz Todt, submitted a most spectacular design: linden trees were to be removed to make way for a ten-lane road. On each side, he envisaged giant high-rise blocks with long roofs where an aeroplane may land.

Competition entry by Cornelis van Eesteren: a tower block with windows and bars, first prize, 1925

Cornelis van Eesteren was a leading figure in the International Congress for New Architecture (CIAM). His design was for a high-rise building situated between the older Prussian and the younger bourgeois halves of the avenue. He positioned parallel running tower blocks on the south side and a continuous high-rise block on the north side.

Unter den Linden with heavy car traffic, 1928

Just a few years before this photo was taken, carriages could still travel on both sides in both directions along Unter den Linden. In the 1920s, the boulevard was made into a dual carriageway, the carriages replaced and cycling prohibited.

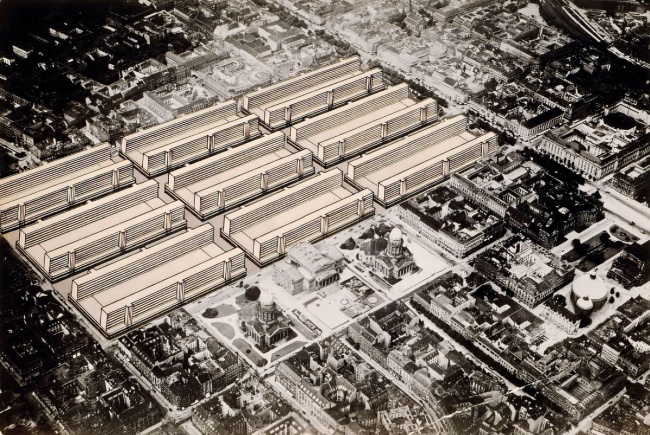

Ludwig Hilberseimer’s Automotive Fantasy

Ludwig Hilberseimer was a key figure of modernist, car-oriented urban planning. His 1924 “high-rise city” and 1929 “city development” are widely known. In 1927, Hilberseimer spoke out in favour of the concept of a multi-level city: “Below, the commercial centre with its car traffic. Above, the residential area with its pedestrian traffic. Underground, long-distance and light rail infrastructure.” He taught urban planning at Bauhaus Dessau from 1929 to 1933. In 1938, he followed Ludwig Mies van der Rohe to Chicago, however by 1963, he was dismissive of his radical plans for Berlin.

Aerial view of the Lustgarten and its surroundings, 17th September 1925

The centre of the new metropolis had already been modernised in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For many architects and planners, the work had not done enough. They pointed to the car-flooded cities of the USA, and called out to create a completely “New Berlin”.

Ludwig Hilberseimer’s “Friedrichstadt Project”, 1928

Nine huge pairs of office buildings were to be built in the place of two blocks each, in this prime central location. Ludwig Hilberseimer confessed on reflection in 1963: “The result was more of a necropolis than a metropolis, a sterile landscape of asphalt and cement, inhuman in every respect.” A rare moment of self-criticism from a planning architect.

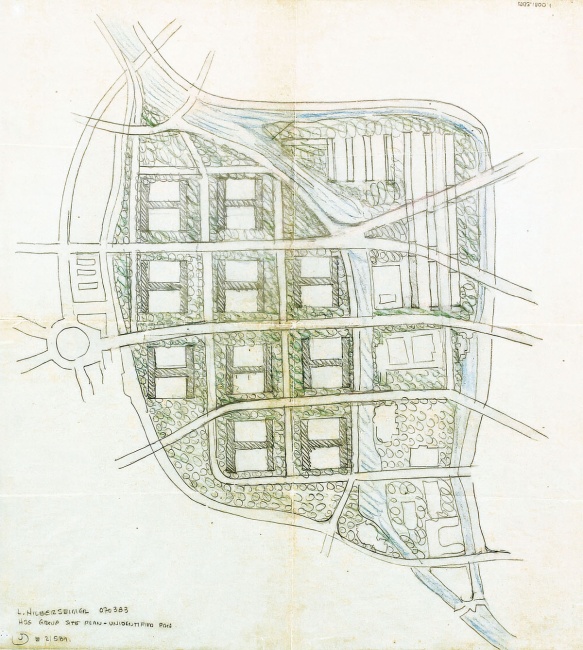

Ludwig Hilberseimer’s environment: sketch of an old town project, 1932/33

Monbijoudreieck was to retain Museum Island, the palace, the Marstall and the Circus Busch only. The east side was to have a simplified layout with only ten H-shaped high-rise buildings – the “H” being for Hilberseimer. The mediaeval old town was to disappear completely.

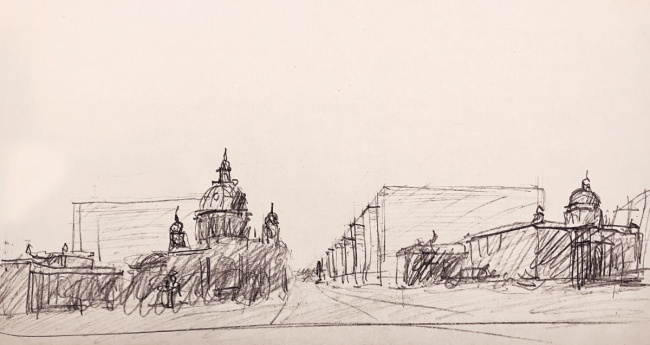

Ludwig Hilberseimer’s environment: View of the new east side of the city centre, 1932/33

Seen from a driver’s perspective, in the foreground from left to right: the Altes Museum, cathedral and palace. In the background the densely stacked, uniform H-shaped tower blocks. St Mary‘s Church, St Nikolai’s Church and the Rotes Rathaus town hall were not spared destruction either.

Lofty Plans for the Automobile

The city council’s plans extended for miles beyond the city centre, even beyond the outskirts of the city. In 1929, the Office for Urban Planning proposed the “Schnellstraßenplan” (motorway plan) – a comprehensive network of ring and radial roads that would extend far into the surrounding countryside. These radial roads, however, did not just lead traffic away from the city centre but also channelled an influx of traffic in. The interwar period is characterised by the traffic planners determination to accommodate and reap the rewards of the increase of traffic, as shown by the 1930 magistrate’s bill.

Martin Wagner and Felix Unglaube: Conceptual sketch for a new Alexanderplatz, December 1928

The two municipal planners reimagined the square in a circular shape, to accommodate traffic. The various traffic types were separated, with space for cars dominating and pedestrians relegated to the perimeter. Barriers positioned in the centre were designed to prevent pedestrians from crossing diagonally.

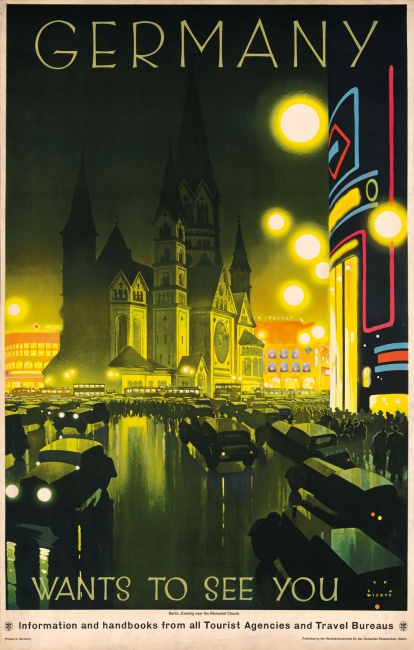

Berlin advertising poster: “Germany wants to see you”

Even the city‘s advertisements were dominated by imagery of cars rolling along shining roads and the fluorescent lights of city nightlife. Here, the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church appears in contrast, remaining in the dark, and local transport and passers-by disappear into the shadows.

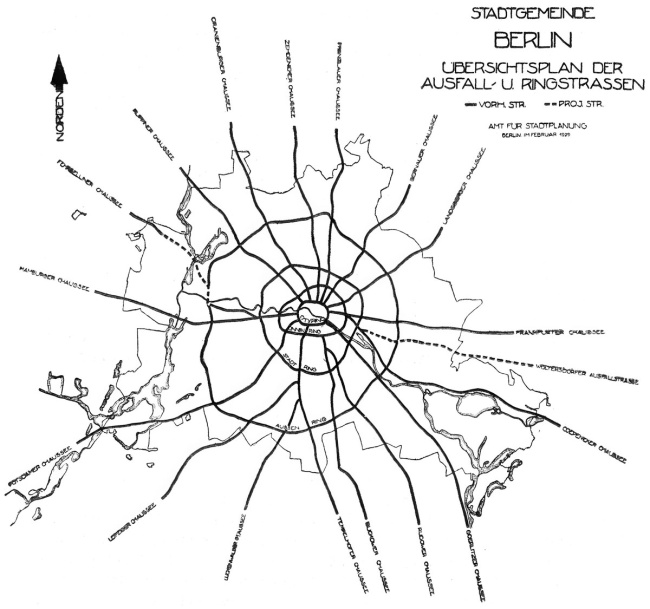

Design for a motorway network for the greater Berlin area, Office for Urban Planning, February 1929

The Office for Urban Planning envisaged a comprehensive network of radial and ring roads. It can be regarded as the first official development plan to make Berlin car friendly. In those years, as later, Berlin became a pioneer of car-oriented urban planning.

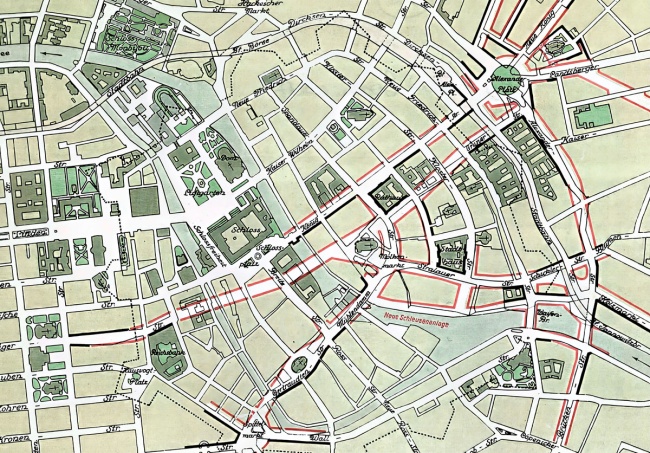

Road construction and road widening projects planned for the redevelopment of the southern part of the old town, 18th April 1930

Paul Wittig, the father of Berlin‘s underground railway network, described the magistrate’s proposal to the city councillors as follows: In order to “open up the historic city centre” in terms of transport, “uninterrupted streets with greater capacity would have to be created.” The „traffic hotspots“ were to be Alexanderplatz, Jannowitzbrücke and Molkenmarkt.

Key Figures

Martin Wagner (1885–1957)

The City Councillor for Building in Greater Berlin from 1926, drove forward the magistrate’s major modernisation programmes. However, his attempts to completely remodel the southern part of the old town failed. His vision for a „cosmopolitan city square“, which he completely changed every few decades, was eventually realised to some extent at Alexanderplatz. He moved to Turkey in 1935 and then to the USA in 1938. Wagner was a member of the Architekten- und Ingenieur-Verein zu Berlin.

Ernst Reuter (1889–1953)

The City Councillor for Transport for Greater Berlin from 1926, together with Martin Wagner and the Councillor for Civil Engineering, Hermann Hahn, pushed for the modernisation of Berlin‘s transport network. During this time, BVG was established, as were the first car-friendly development plans. In 1931, Reuter became Lord Mayor of Magdeburg, and in 1935 he went into exile in Turkey before becoming Lord Mayor of West Berlin in 1948.

Richard Ermisch (1885–1960)

The architect and building official worked throughout the Weimar Republic and during the Nazi era before becoming an urban planner for the Berlin city council after the war. During the Weimar Republic, he planned the redevelopment of the southern part of the historic city centre. He continued to work on this project after 1933 and in parts even after 1945. Ermisch was a member of the

Architekten- und Ingenieur-Verein zu Berlin.