Bundesallee in West-Berlin

Cars, Cars Everywhere

The 1960s marked the peak of West Berlin’s transformation into a car-oriented city. It precipitated not only the planning and construction of an inner ring road, but the expansion of the Bundesallee into a dual carriageway. From 1872 the road that became Bundesallee (renamed in 1950 from Kaiserallee), linked two important areas; an aspiring centre at Auguste-Viktoria-Platz (now Breitscheidplatz) and a route running from the city, the Berlin–Potsdamer Chaussee (now Rheinstraße). The main road stretched to 3.7 kilometres, and served as a central element of an ambitious project named after Johann Anton Wilhelm Carstenn, the urban developer from Hamburg. The geometric layout and characteristic green spaces of the area’s “Carstenn Figure” is one of the most important testimonies to Berlin’s urban development. However, much of this was lost in the 1960s, during the drive towards car-first infrastructure. Little remains of the leafy plazas built by Richard Thieme, the landscape architect for Wilmersdorf. The change is stark on Bundesallee, where the original design has been eroded away with the addition of tunnels, ramps, and pedestrian diversions.

Opening of the traffic tunnel at Bundesplatz, 4th March 1967

The destruction of the Bundesplatz to make way for the construction of a traffic tunnel was widely celebrated at the time. Never again would pedestrians come here in such large numbers as attended the inauguration.

The Road and its Structures

In 1950, to mark the opening of the Bundeshaus at number 216-218 Kaiserallee, the road was renamed Bundesallee. With this change came the wish that “Berlin [...] might be part of Germany and become the capital of the country” (Willy Brandt). Between 1958 and 1965, there were twelve distinct plans for redevelopment along Bundesallee implemented by the Senate Building Director Rolf Schwedler. The road was to be widened and the gaps between the buildings and street corners were to be filled with recessed residential and commercial buildings. Huge buildings such as the ADAC office, the Berlin Sparkasse headquarters and the Wohnbaukreditanstalt [housing loan association] were given pride of place.

View of the residential tower block on the corner of Berliner Strasse and Bundesallee, after 1966

Another junction stripped of its charm, the buildings levelled. The loss of BeBa-Palast and other grand buildings was needed to dig the Wilmersdorf Tunnel. Today a high rise residential block, designed by architect Helmut Ollk, sits at 41 Bundesallee.

View of the office and residential building at 219–220 Bundesallee, after 1965

This new building is confidently positioned between landmark historic buildings. Designed by Helmut Ollk, this same plan was realised so many times along the road that by the mid 1960s, Bundesallee was referred to as “Ollk Avenue”.

The ADAC building at 29–30 Bundesallee by Willy Kreuer (with Herbert Stranz), after 1961

Car registrations rose steadily in the 1950s, as did the number of ADAC members. With over one million road accidents recorded in 1961, Europe’s largest automobile club demanded road safety education be given to children.

Aerial view of the Sparkasse headquarters, 171 Bundesallee, by Günter Behrmann, 1968

The ten-storey headquarters with a banking hall arranged over two floors was officially opened on 2nd July 1965, before the construction of the tunnel was finished. The construction equipment for the Wilmersdorf Tunnel stretches out in front of the building.

The drive-in banking counter of the Sparkasse of the City of West Berlin at 171 Bundesallee, 1965

Drive-in: Customer service is our top priority! Up to a maximum height of 2.40 metres.

The so-called “bank on wheels” at the Sparkasse headquarters in Berlin-West, Bundesallee on the corner of Badensche Strasse, 1969

Around 1970, this mobile Sparkasse bank would travel around Berlin, until the city was covered by branches.

Gardens, but for Cars

The squares of Friedrich-Wilhelm-Platz and Bundesplatz have managed to keep some of their original perimeters and historic proportions. However, the north of Bundesallee has been significantly widened, and augmented with its recessed post-war buildings. At the northern end, eight streets converge in a sweeping intersection, known locally as The Spider. According to the original plans, a fly-over was designed to emerge from the wide grass verges into Meierottostrasse, in order to bypass City West. None of the original spatial planning of the square remains due to extensive modifications made for car traffic.

Aerial view of the areas marked out for the fly-over at the Bundesallee/Hohenzollerndamm junction, 1976

The longstanding vision of building both an overpass and tunnel was abandoned in 1979. By then, already 30 plots at “Spichernplatz” had been flattened. The junction today has an expansive central island, used for car parking.

The first foundations at Bundesplatz for a road and rail tunnel, early 1960s

Digging the tunnel would mean many years of noise and interruptions for the long-suffering residents of Buddelplatz (as Bundesplatz was known locally). The construction companies built a reputation for their total lack of compassion.

Aerial view of the Bundesallee looking towards Rheinstraße and Steglitzer Kreisel roundabout, 1976

The stem has snapped: the ornamental plaza that surrounded the Zum Guten Hirten church is now intersected by a six lane carriageway. What remains of the plaza has been adapted in “living room style” with low walls and benches.

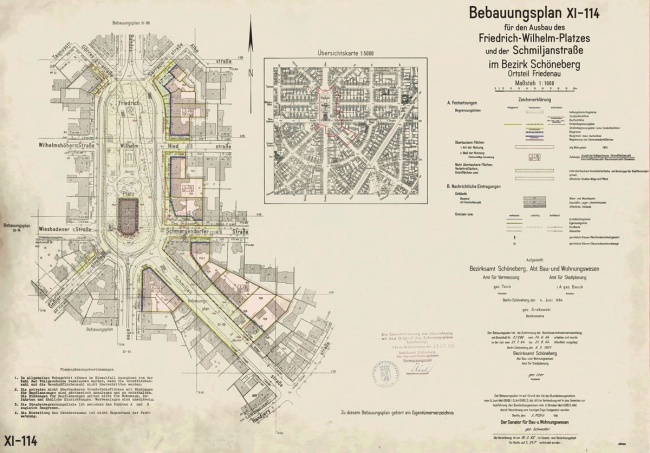

Plan for the expansion of Friedrich-Wilhelm-Platz, 1965

Connecting Schmiljanstrasse and Bundesallee destroyed the plaza, and more. Seven buildings and their gardens were to be torn down. Only two of these remain, and now hold heritage status.

Tunnels and Bridges

According to the traffic plans, different “road levels” were needed on the “main connecting route” of Bundesallee, so that cars would flow “without crossroads.” Opened in 1967, the Bundesplatz tunnel was to relieve a “junction with heavy turning traffic” while the second Wilmersdorf Tunnel was to pass under two intersections and connect the official government offices of Schöneberg Town Hall with Fehrbelliner Platz. In 1971, a footbridge was raised from Volkspark over Bundesallee, which still had few pedestrian crossings.

Seen from below: the northern ramp of the Bundesplatz tunnel under construction, 1964

The photographer is standing under the centre of what was once a leafy square. The image is captured at the mouth of the tunnel looking directly into the deserted 162 metre ramp, a view reserved for motorists.

Seen from above: the northern ramp of the Bundesplatz tunnel under construction, 1964

“It will connect the city centre to the western bypass without crossings!” Naturally, this meant only good news for motorists. The 600 metre long, 20 metre wide tunnel hindered foot traffic, and stretched for vast distances with no pedestrian crossings.

The central support for the Bundesplatz tunnel for the S-Bahn ring, 1966

Preparations for a central tunnel ran parallel to the construction of the S-Bahn line 9. The S-Bahn bridge was widened and supported in the middle. The deep concrete structure also serves as the central wall of a tunnel for two-way traffic.

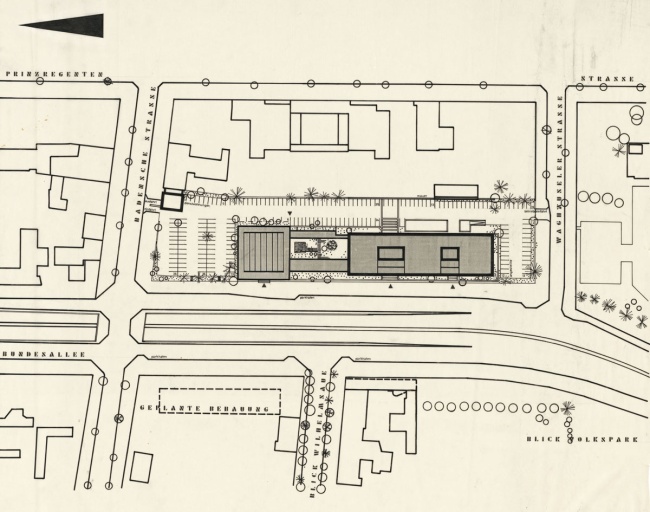

Competition entry by Herbert Stranz for the new headquarters of Berlin’s Sparkasse, before 1965

By the time the competition was announced, the plan for the Wilmersdorf Tunnel had been completed. This meant that the plans could be used as the basis for the competition designs. The entire outdoor area was reserved for cars.

The Volkspark footbridge above the Bundesallee, 1975

With the opening of Berlin’s first cable-stayed bridge in 1971, the pedestrian link between the two sides of Volkspark intersected by the motorway was reestablished. In good weather, the narrow four-metre wide footbridge can become crowded.

Grand Plans for a Car-Friendly City

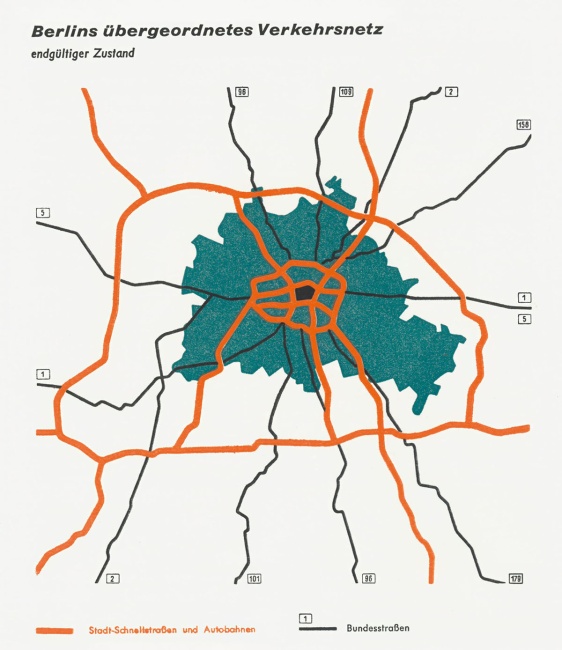

Two years after the Second World War had ended, the S-Bahn network was – mostly – back up and running. And yet, city planners were fixated on making the city more accommodating for cars. After the division of the rail network along with the rest of the city in 1961, the 1965 “land-use plan” was focused on extensively reconstructing the Berlin city highway. Growing the network of bypasses and arterial roads was a priority, as well as expanding main roads into massive motorways. West Berlin’s tram system was abandoned in 1967, replaced by new underground lines and buses.

Highway planning for the area around Berlin, as of 1957

Around the same time as the International Building Exhibition (Interbau) in 1957, radical plans were in motion to reshape Berlin’s transport network between East and West. The centre of the city was to be surrounded by four motorways which would be supplemented by major arterial roads.

Opening part of the West Berlin Motorway, 19th December 1962

The northern section of the motorway was opened by the Minister of Transport Hans-Christoph Seebohm, the Governing Mayor Willy Brandt and the Senate Building Director in West Berlin Rolf Schwedler.

A farewell to the last tram, 2nd October 1967

In around 1865, the first horse-drawn tram made its way from the Brandenburg Gate to Charlottenburg and by 1900, the entire tram network had been electrified. By 1967, after the division of the city, all tram lines in West Berlin were decommissioned.

Motorway junction at Oranienplatz in Kreuzberg according to the West Berlin land use plan, 1965

The Oranienplatz would have disappeared under a gigantic motorway junction in the shape of a turbine. The two city motorways “Südtangente” and “Osttangente” would have crossed here. In 1970, the turbine in the plan was replaced in favor of a simplified “cloverleaf solution”. The motorway planning was not abandoned until the 1970s.

The motorway junction at the Funkturm radio tower shortly before its completion, 1971

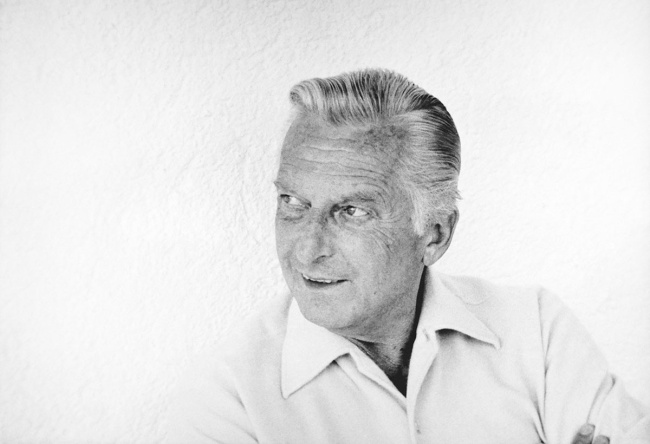

This image comes from the colour slide collection of Rolf Goetze. A native Berliner, author of radio plays broadcast on the American radio channel RIAS, contributor to the “Tagesspiegel” newspaper, and in his later days, Goetze became programme director of the Urania. It was he who captured this image of an “aggrieved city” (1950-1980).

A Singular Figure in the Urban Landscape

As early as 1872, the city planner Johann Anton Wilhelm Carstenn and architect Johannes Otzen had planned a housing development with a connecting railway outside of Berlin’s busy centre. The characteristic system of squares and streets they envisaged is still seen in the area’s layout today. The construction of the Joachimsthal grammar school (1880) in the north, the Zum Guten Hirten church (1893) in the south, and the carefully designed green spaces invigorated this development while it gradually filled with new buildings and the bustle of everyday life. Erich Kästner’s children’s novel “Emil and the Detectives” (1929) tells us quite how lively the area was.

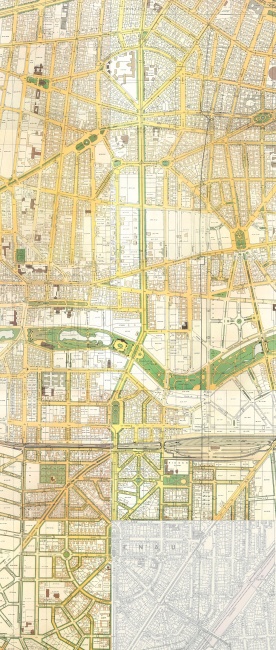

Drawings for the “Carstennian Figure”, published by Julius Straube, 1907–1914

The maps created for the town of Wilmersdorf depicted the “Carstennian Figure” in almost perfect detail. They feature sophisticated but never fully realised landscape design from landscape architect Richard Thieme.

Friedrich-Wilhelm-Platz: the Zum Guten Hirten church by Ludwig Meidner, 1913–1916

The plaza at southern Bundesallee featured prominently in a painting by the leading exponent of urban expressionism. He seemed to foreshadow the destruction of Friedrich-Wilhelm-Platz in his “Apocalyptic Landscapes”.

Gardens along Kaiserallee, postcard from before the First World War

When the Joachimsthal grammar school vacated its premises, Meierottopark was transferred to the town of Wilmersdorf. Richard Thieme laid out plans for a promenade shaded by trees, pictured here with a view of the Carstennian development on Pariser Strasse.

Kaiserplatz as seen from the south-east, 1912

In 1910, the town of Wilmersdorf purchased a sculpture titled “Winegrower” from the estate of the artist Friedrich Drake. Richard Thieme specially redesigned Kaiserplatz to showcase the sculpture, preserving it as both an ornamental and functional square.

The southern end of Kaiserallee looking towards Friedrich-Wilhelm-Platz, 1931

The 45-metre-wide street is lined by young trees. Only 15 metres of this width belonged to the carriageway, where the tram ran along the central axis. Each pavement was 15 metres wide with large gardens running along the buildings.

“Emil and the Detectives”: Advertising pillar on Kaiserallee, 1929 (or 1931)

“In Trautenaustrasse, on the corner of Kaiserallee, the man in the bowler hat disembarked the tram. […] The hideout was perfect – between the kiosk and an advertising pillar. […] All of a sudden, a horn honked behind Emil!”

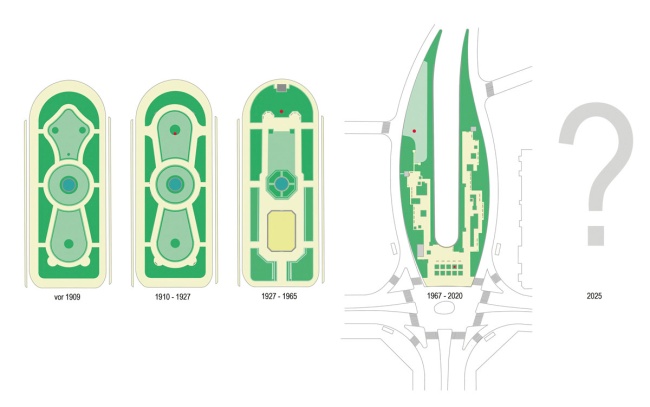

Kaiserplatz/Bundesplatz – the centrepiece of a complete work of urban art!

During his time in office, Wilmersdorf landscape architect Richard Thieme carefully transformed Kaiserplatz into a modern town square. Now called Bundesplatz, the square has been all but destroyed by the motorway tunnel. Who will have the final say?

Key Figures

Helmut Ollk, Architect (1911–1979)

After studying architecture, the trained builder co-founded the BDA (Association of German Architects). In the post-war period he was a successful architect in West Berlin. Bundesallee, lined with many of his residential and commercial buildings, was known locally as “Ollk Avenue”.

Rolf Schwedler, Building senator (1914–1981)

The longest-serving senator in the history of West Berlin was a qualified civil engineer, responsible for housing and development between 1955 and 1972, as well as for transport and operations from 1967 onwards. His time in office was characterised by demolition and redevelopment as well as the expansion of West Berlin into a car-oriented city. Schwedler was a member of the Architekten- und Ingenieur-Verein zu Berlin.