Kurfürstendamm

Inventing the Neuer Westen (New West)

The City West is a unique development, known as a “place without history”; it quickly sprouted to become the unquestionable centre of a new kind of city. Only years before, the area had lacked a sense of neighbourhood, without a town hall or high street to speak of. It was not until 1882 that this area, called the “Neuer Westen” (New West) started to come together, heralded by the completion of a train station connecting the people of Berlin to a place that had been regarded as far outside the city limits. The Zoologischer Garten station encouraged people to visit two important destinations sitting to the west of the Tiergarten; the Berlin Zoo (opened 1844) and the Hippodrome (opened 1846).

The construction of Kurfürstendamm was a cornerstone of the rapid development of this district, which was separated by the Tiergarten from Berlin proper. Kurfürstendamm is built in the grand Parisian style, an imposing 53-metre-wide boulevard whose design is credited to an intervention by the Imperial Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. In 1882 the Kurfürstendamm-Gesellschaft (Kurfürstendamm Company) was established to engineer the road and develop the surrounding land, which stretched from the city and ended at a number of new mansions situated in the historic royal hunting grounds of Grunewald. The boulevard was completed on 5th May 1886. Its designer, Hugo Hanke, was a local politician and member of the Architekten-Verein zu Berlin, as well as a director of the Kurfürstendamm Company.

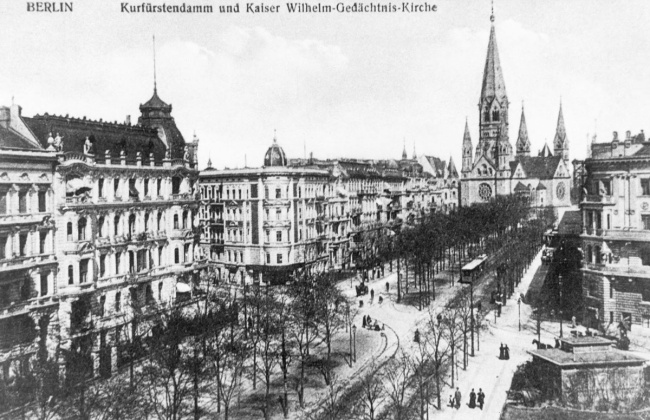

Auguste-Viktoria-Platz around 1896

The original Romanisches Haus [Romanesque House] stands in the centre, with the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church (architect Franz Schwechten, 1895/96) to the right. In 1901, a second Romanisches Haus – known for its famous Romanisches Café – was built to complete this thriving centre known as the “City West”.

Beginnings and Endings: the Church and the Lake

The main stretch of Kurfürstendamm extended for a good three kilometres between the Romanisches Forum at Auguste-Viktoria-Platz (Breitscheidplatz since 1947) and the western end at Lake Halensee. Both were important landmarks. The Romanisches Forum served as the highlight of urban development in the Neuer Westen, where the internationally regarded Romanisches Café became the epicentre of a vibrant artistic and cultural scene that shaped the character of the promenade. The terraces at Lake Halensee, known as “Lunapark” from 1909, offered amusements and attractions which brought countless day trippers.

Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church on Auguste-Viktoria-Platz, around 1895

This entire neo-Romanesque ensemble (the “Romanisches Forum”) was created as a stage for imperial state occasions (architect: Franz Schwechten).

View from Hardenbergstrasse towards Auguste-Viktoria-Platz, around 1906

Left: the exhibition rooms of the zoo, built 1905/06 in the neo-Romanesque style (architect: Carl Gause). To the right of the church is Kurfürstendamm.

The terraces at Lake Halensee in 1912

Kurfürstendamm was a direct connection to the park on Lake Halensee, which became a popular weekend destination from 1904 onwards. After it was named the “Lunapark” in 1909, it transformed into an amusement park that stood until 1939.

The Neuer Westen Promenade

Kurfürstendamm had quickly become a much sought-after address. Wealthy families and cultural figures moved into buildings with lavishly decorated façades and large elegant apartments. At street level, a thriving commercial community developed and the restaurant industry began to flourish. Tradespeople had started to move into the area, to escape the crowded centre of Berlin. An exciting feeling of dynamism in the “New West” has been stoked by the many theatres, cabarets and fledgling cinemas in the area, along with the completion of an electric streetcar network in 1900.

View from Kurfürstendamm towards the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, around 1910

Gardens grew in front of the buildings prior to the First World War, but these disappeared as shops and restaurants opened along the street. Here, the upper floors boasted living arrangements that were large and opulent.

Kurfürstendamm on the corner of Joachimsthaler Strasse, around 1910

Opened in 1886, the monumental 53-metre-wide street was considered an avenue without being named as one. It became a busy route, offering a central bridleway, and a streetcar rolling along the sides. Lanes for carriages were added, as well as pedestrian paths.

Joachimsthaler Strasse on the corner of Kurfürstendamm, looking towards Zoologischer Garten station

In 1920, the Größenwahn cabaret moved into the corner building on the left (architect: Christoph Osten, 1894). The famous Café Kranzler took over its premises in 1932. Today, Café Kranzler is found in the rotunda of another building (architect: Hanns Dustmann, 1958).

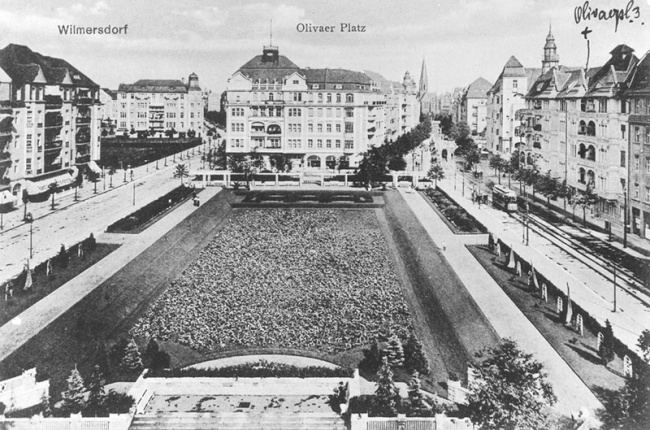

Olivaer Platz, close to the middle of Kurfürstendamm, looking east, 1914

The square was originally designed in 1892 as a recreational area. It was rebuilt between 1907-1910 by the landscape architect Richard Thieme. Thought of as the most modern square in Berlin, it had symmetry, unusually generous flower beds, and a children’s playground. Kurfürstendamm stretched behind the buildings on the left.

Kurfürstendamm at the corner of Westfälische Strasse at the time of the Kaiser

This junction is located at the western end of Kurfürstendamm, before Lake Halensee. Seen here is the streetcar that ran along Kurfürstendamm.

The Cost of the Road: the Villa Complex

It became apparent that few people would invest in a road that tapered into the wilderness – and so a series of lavish villas were designed to elevate the status of Kurfürstendamm. In 1882, and with investment from Deutsche Bank, the Kurfürstendamm Company was granted a 234-hectare area of the Grunewald to construct a suburb. The development stretched between Lake Halensee and Lake Hundekehlesee, and it was the company’s core responsibility to construct and sell the properties. Building work progressed rapidly. By 1897, 205 of the villas were occupied, accompanied by the birth of a lively social scene, the exclusive preserve of the upper class.

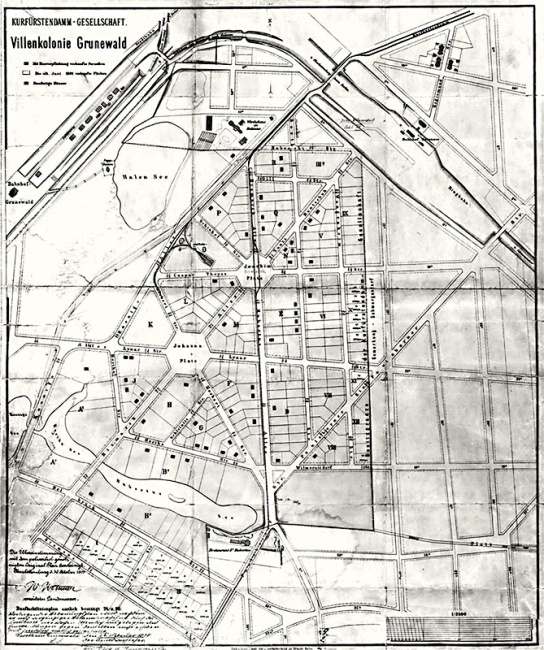

The Kurfürstendamm Company plan for the Grunewald villa development, 1899

Against the wishes of the Berlin magistrate and the forestry commission, the Kurfürstendamm Company was allowed to develop a 234-hectare area of forest situated at the planned end of the road.

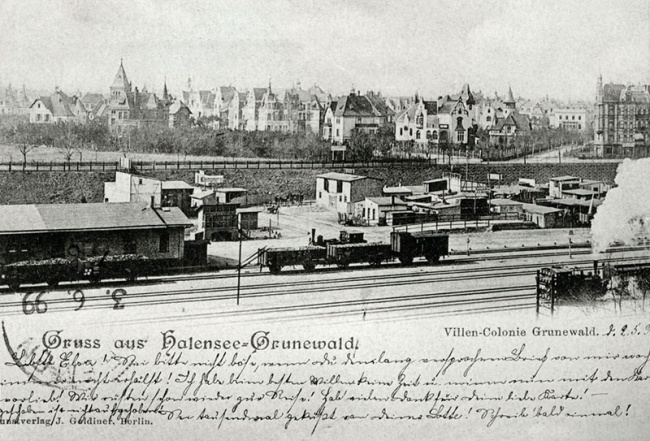

Halensee freight depot, pictured in front of the Grunewald suburban development, 1898

The development grew quickly and became extremely sought-after. Building prices climbed from 8.30 to 15.40 Marks per square metre within ten years. The Grunewald soon became the most expensive and desirable district in the greater Berlin area.

Aerial view of Lake Diana from the south-east, 1919

Four artificial lakes were created to increase the desirability of the properties in the new suburb. One of these, Lake Diana is pictured here.

The Kurfürstendamm Company office at 18 Herthastrasse, 1892

There was a lively social and cultural life to be had between the villas and clubhouses, which ranged in style from country houses to palace-esque. The Kurfürstendamm Company inhabited one of the villas as offices.

The Young Centre of the Capital

The new precinct was developing rapidly, with changes marked by the opening of the Zoologischer Garten station and the establishment of the Royal Technical University in the nearby city of Charlottenburg. Meanwhile, the bustling government and administrative district of Berlin was also expanding, causing residents to move out of the city and into new areas such as Kurfürstendamm. New residents were welcomed by the smaller towns outside the city limits, especially by the local tax authorities, who remained independent until the formation of Greater Berlin in 1920.

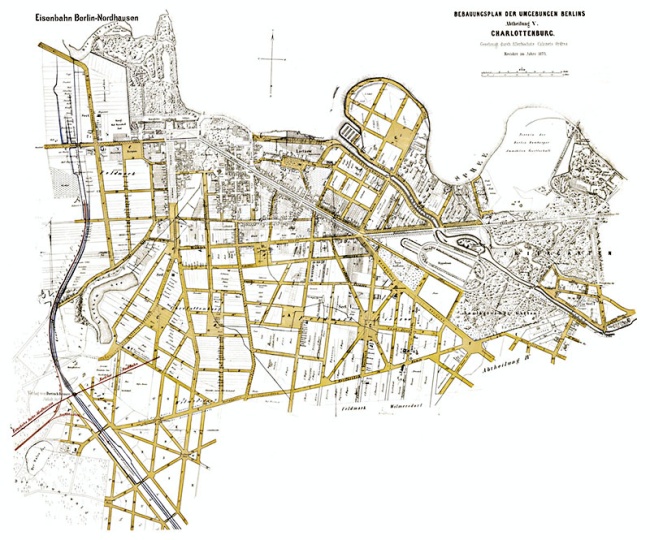

Development plan for the “New West” based on the Hobrecht plan, 1873

Auguste-Viktoria-Platz, marked “F” is found to the bottom right. Owners and developers, including the architect August Orth, are listed by name in the building plots. It was not uncommon for the architects of the development to privately invest in properties.

Zoologischer Garten station, 1903

The opening of the Zoologischer Garten station in 1882 was crucial for the development of Kurfürstendamm and the entire “New West”, providing access to new residential areas and recreational opportunities.

Construction site of the Royal Technical University of Berlin, before 1884

The new building of the largest technical college in Prussia at the time was inaugurated in 1884, spurring the development of a dormant suburban area. The construction of the university involved some of the most famous architects of their time: Richard Lucae, Friedrich Hitzig and Julius Raschdorff. The main campus of the Technical University of Berlin is still located on this site.

Kurfürstendamm, 1880s

Very quickly villas cropped up along the previously undeveloped rural bridle way, however these were soon replaced by palatial multi-storey residences.

Villa Raussendorff by architect Hans Grisebach, 1891

The first buildings on Kurfürstendamm were spaciously designed detached houses. In time, most of these were demolished to make way for upmarket apartment buildings with as many as 15 rooms. Only two of the historic villas remain today.

After the Second World War: Showcase of the West

After the Second World War, Kurfürstendamm would drastically change, with its magnificent buildings now lying in ruins. The Jewish population had been purged, and would not return. A strong desire to restore the district to its “golden age” quickly emerged, and to regain a reputation of international prominence. A period of reconstruction followed, focused on simple, straightforward design, and car-oriented planning. Soon, Kurfürstendamm was once again a wonderful place to live. It was the centre of West Berlin until the fall of the Wall in 1989, and attracted tourists, cultural workers and flaneurs. In 1999, an urban masterplan for the area around Breitscheidplatz was set in motion. The “Plan for the City Center” was initiated by Hans Stimmann, the Senate Construction Director. Together with Alexanderplatz and Potsdamer Platz, this area was to be shaped by high-rise buildings as an expression of the resurgence of the reunified city.

Aerial view of Rathenauplatz, 1958

The post-war period was dominated by plans to make Berlin more car friendly. In the centre of the picture is the mouth of the Rathenau Tunnel (part of the city highway), with the radio tower in the background.

Aerial view of Breitscheidplatz with a view over the “Zentrum am Zoo”, 1971

The centre of West Berlin was completely redesigned in the 1950s. Behind the Memorial Church stands the Schimmelpfeng-Haus (1957-1960), to the right the Huthmacher tower block (1955-1957), in front the Zoo Palast cinema (1956/57) and Bikini-Haus (1955-1957). Famous architects of their time were at work here: Franz-Heinrich Sobotka and Gustav Müller, Paul Schwebes, Hans Schoszberger, and Gerhard Fritsche.

The Kudamm Corner, Werner Düttmann and others, 1974

These four interlocking cubes replaced the war-damaged ”Grünfeld-Eck” shopping centre, which was demolished in 1968. This new shopping centre was considered an eyesore by many; it no longer exists today.

Kudamm as a cultural mile: Haus Wien with the Vienna Film Theatre, 1958

Opened in 1913, the Union Palast cinema was one of the first dedicated movie theatres in the city, designed by architects Günter Nentwich and Erich Simon. The listed building was rebuilt after the destruction of the war and served as an important venue for the international Berlinale. Since 2001 its use has been purely commercial.

Kudamm as a catwalk: fashion show 1960

After the Second World War, “Kudamm” became West Berlin’s centre of fashion, culture, and flaneurs.

Kudamm as a political stage: demonstration by the Citizens’ Committee for Transport Policy, July 1972

Much like today, in the early 1970s there were protests by what became the Westtangente citizens’ initiative against the plans for car friendly infrastructure. These were levied especially against urban motorways such as the Westtangente.

Redesign of the area between Breitscheidplatz and Bahnhof Zoo according to the 1999 city plan

After the reunification of Berlin, City West was redesigned for a third time, except now with high-rise buildings: at the back right is the “Zoofenster” (2012) designed by Mäckler Architeckten; at the back left the “Upper West” (2017) designed by Langhof/KSP Engel. Further to the left, the “Neues Kranzler-Eck”, designed by Murphy Jahn Architects, which has been standing since 2000.

The former Kudamm-Karree in its newly proposed form

After seven investors pulled out, the architectural firm Kleihues + Kleihues is now remodelling the block. The new square is currently called “Fürst”. The development will include the renovation of the high-rise, moving the Theater am Kurfürstendamm back to its original location and opening up the site to face Kurfürstendamm.

Key Figures

Hugo Hanke (1837–1897)

Hanke was a member of the Architekten-Verein zu Berlin, he made a significant contribution to the rapid development of Kurfürstendamm as a property developer and member of the Berlin City Council. The Kurfürstendamm Company negotiated the title to approximately 155,000 square metres of land on behalf of Deutsche Bank. Hanke conducted the negotiations as a Technical Director of the company, and in return received permission to operate the horse-drawn railway.

Franz Schwechten (1841–1924)

Both an architect and a professor at the Charlottenburg Technical College, Schwechten won the Schinkel Competition in 1868, and was a member of the Architekten-Verein zu Berlin. He is best known as the creator of Anhalter Bahnhof, buildings for AEG and, above all, the Romanesque Forum (1891-1901) which surrounds the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church on Auguste-Viktoria-Platz (now Breitscheidplatz). The ruins that remain only hint to the lost grandeur of the Forum’s highly desirable, somewhat controversial neo-Romanesque design.

August Aschinger (1862–1911)

Together with his brother Carl, Aschinger ran a business consisting of numerous beer halls, patisseries and restaurants. By 1900, he owned one of the largest catering businesses in Europe. He set up the terraces at Halensee, however the “Luna Park” was operated by an assortment of other companies on the same site.