Allee Unter den Linden

Schinkel’s Berlin

Following the Thirty Years’ War, Berlin rose to prominence as the capital of Prussia. The city was transformed into a glittering metropolis by its various kings and electors. The old castle was transformed into a vast and splendid palace, onto which Unter den Linden led from the west. The avenue was the first of its kind in Berlin, extraordinarily wide and host to myriad trees. Despite its humble suburban origins, Unter den Linden became a blueprint for future thoroughfares. It was not until the 18th century that grand buildings started to appear on the road, including the Zeughaus (Armoury), opera house, and university. It became the location of the ceremonial march for the Prussian royal family and a stage for the ruling classes and military. The ends of the avenue to both the east and the west are public spaces that are among the most notable of the city: the Lustgarten (Pleasure Garden), and Pariser Platz housing the Brandenburg Gate. Karl Friedrich Schinkel was the main architect and Unter den Linden remains the most important example of his urban design.

Military parade in Berlin, 1837

Troops march west in formation across Opernplatz towards the palace. However, the focus of the picture is not on the military display but on the diverse gathering of Berlin society at Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s Neue Wache (New Watchhouse). The painter offers this captivating view of Unter den Linden, flanked by its grand buildings.

Stately Homes

At the turn of the 17th Century, the first military buildings such as the Zeughaus (Armoury), the residence of the Berlin Commandant, as well as various noble and royal residences were erected to the west of the palace and by the bridges of the Spree at Lindenallee. Later, Frederick II unveiled various cultural buildings along the avenue, such as the opera house, the library, and the later university. Together with the Cathedral, they formed the so-called Forum Fridericianum (Frederick’s Forum), the Opera Square. The vast with of the lime-tree lined avenue allowed for other squares to form such as at Schinkel’s Neue Wache and in front of the Zeughaus. Only the four cornered Pariser Platz had its own distinct boundary.

The Lustgarten in front of the palace, 1881

The long palace façade and Schinkel’s many buildings framed the Lustgarten, which became a key setting for ecclesiastical, political, and military displays of prowess. Designed by Schinkel as an ornamental plaza, this place played host to the grandiose victory parades of the later Prussian Wars (1864-1871).

Unter den Linden, from a map of Berlin by Jean Chretien Selter, 1846

This avenue was a powerful dominating feature of Berlin thanks to its vast proportions and impressive lime trees, buildings and squares. Its importance is indicated by the number of ceremonial processions and demonstrations that took place there, as well as being the site of the 1933 book burning.

The Brandenburg Gate at Pariser Platz, erected from 1788 to 1791, pictured 1906

Carl Gotthard Langhans modelled the Brandenburg Gate on the ancient Propylaea in Athens. This outstanding example of early neoclassical architecture became the hallmark of Schinkel’s classical Berlin, known as “Spree-Athens”. Bearing witness to much of the city’s tumultuous history, it remains a site for major events today.

The square at Neue Wache, 1881

The square in front of the armory has a palpable military atmosphere, characterised by its monuments of Prussian generals, marching bands, and as the site of the ceremonial changing of the guard. Today, the Neue Wache is once again a tribute to the victims of war and tyranny, as it was during the Weimar Republic.

Equestrian statue of Frederick II, at Unter den Linden

The important equestrian statue of Frederick the Great was created by Christian Daniel Rauch for the “Forum Fridericianum” and inaugurated in 1851. View from the enclosed central area of the Lindenallee to the east. Visible on the left are the armory, in the center the palace and in the distant

background the town hall tower.

Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s Major Works

The fall of Napoleon precipitated great political and economic uncertainty, and during this period in 1816, Karl Friedrich Schinkel began work on his extensive architectural projects. These included nearly 20 works on Unter den Linden and the Lustgarten. As well as the buildings themselves, Schinkel also designed the interiors of various royal and noble residences, including apartments, palaces and the Neue Wache. He also built a bridge for Unter den Linden, the Schlossbrücke that connected the palace to the court church and the Royal Museum. For these projects Schinkel commissioned

pieces from renowned sculptors and painters.

The Neue Wache, built from 1816 to 1818

The first of Schinkel’s state commissions along Unter den Linden began in 1816 with the Neue Wache (New Guardhouse). The architect positioned a Doric columned hall with a sculpted pediment at the front of this large, rectangular neoclassical building. The interior was originally designed to house the Royal Guard.

Altes Museum, built 1822 to 1824

As a feat of urban planning and architecture, this art museum, which opened in 1830, is one of Schinkel’s greatest masterpieces. It features an extensive columned hall which ends with a sweeping staircase that then leads to an enclosed rotunda, and borders the Lustgarten to the north.

The old protestant cathedral, the Berliner Dom, rebuilt between 1818 and 1822, pictured around 1885

Despite an ambitious plan, Schinkel’s reconstruction of this baroque church yielded a modest result. The renovation, with its imposing cupola and portico, was considered an interim measure that would eventually have to make way for today’s gargantuan building, built in 1888.

The Schlossbrücke bridge, built 1822 to 1824, pictured 1875

This bridge masterfully combines architecture and sculpture. Its cast iron railings flank high pedestals adorned with mythical creatures. After Schinkel’s death, groups of allegorical heroic figures were added in tribute to the Napoleonic Wars of Independence.

The 1819 Neue Wilhelmstrasse bridge, pictured 1865

One of Schinkel’s most innovative projects was the structure he built on the narrow Neue Wilhelmstrasse, later demolished in 1867. This piece of classical gabled architecture offered something novel to Berlin, a bazaar of shops on the ground floor.

The Palace of Count Redern, built 1833, pictured 1905

This stately home was reminiscent of a Florentine renaissance palace, built on a prominent corner of Pariser Platz. In 1910, it was replaced by the Hotel Adlon, a sign of the declining esteem in which Karl Friedrich Schinkel was held in the late imperial era.

The Unbuilt Utopias of Karl Friedrich Schinkel

Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s original designs for Unter den Linden were extravagantly elaborate, and were rejected by royal contractors on account of cost. Plans were abandoned for the public library, a monument to Frederick the Great, a highly anticipated palace at Forum Fridericianum for the future Emperor Wilhelm I, as well as a magnificent department store. In the cases of the palace and the Singakademie, each was realised according to more

economical plans submitted by competing architects.

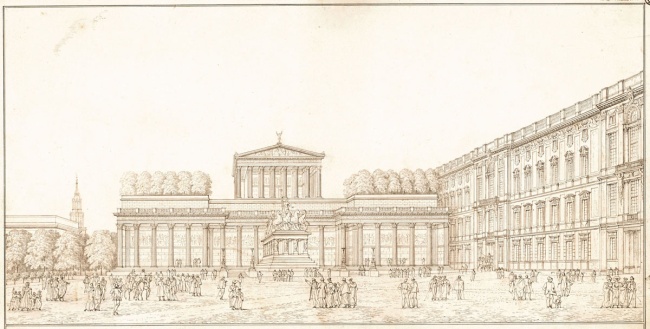

Design for a monument to Frederick the Great, 1832

The futile efforts of his teacher Friedrich Gilly to create a monument to Frederick the Great, prompted Schinkel to create his own design. Planned for the Lustgarten, between the palace and the cathedral, Schinkel designed a monumental columned structure in a strictly classical style, behind which the old Berlin would vanish.

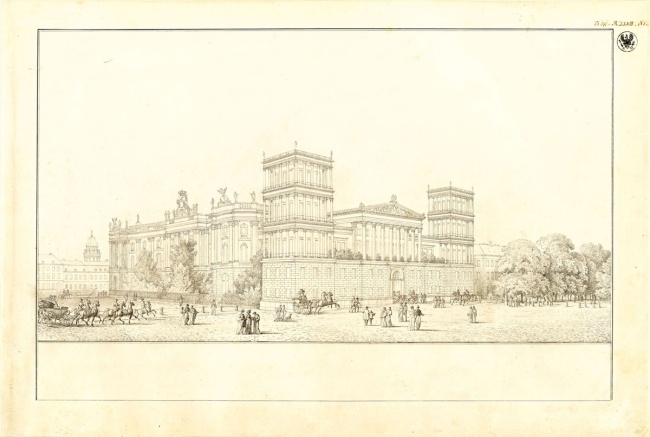

Design for the palace of Prince Wilhelm, around 1829

Schinkel designed two spectacular examples of neoclassical architecture for the palace of the future Emperor Wilhelm I at the Forum Fridericianum, including one with a pillared façade and imposing towers at each corner set on tall plinths and temple front. The existing Old Palace was created by Carl Ferdinand Langhans by 1837.

Design for the Royal Library, 1835

Among the new public buildings intended for Unter den Linden was the Royal Library. This brick design conceived in 1835 is reminiscent of the Berlin Bauakademie as well as mediaeval Marienburg in East Prussia, which Schinkel admired.

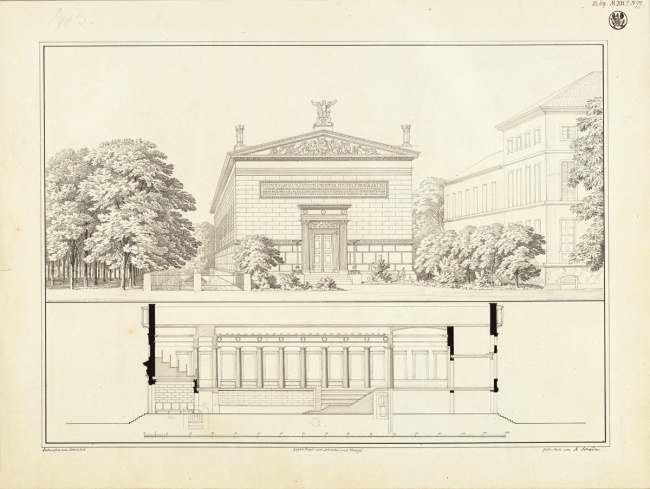

Design for the Singakademie, 1821

Whilst Schinkel’s design was not realised on account of cost, it served as a useful guide for Carl Theodor Ottmer who designed today’s Maxim Gorki Theatre, built in 1824. The most visible similarities are seen in the neoclassical façade, crowning triangular gable and elongated auditorium.

Design for a department store on Unter den Linden, 1827

The design for a “department store” in 1827 was well ahead of its time. It featured large “display windows”, highly practical iron columns, and flattened domes in its interior. These structural features work together with the traditional three-winged palace layout to create a harmonious piece of architectural design.

Plans, Trees and Palaces

Early maps demonstrate the extraordinary, wide proportions of Unter den Linden. From as early as 1688, the avenue served as one of the main corridors of the westward expansion of the city. Cross-sections of the street show the various rows of trees. The eastern section of the street housed state buildings and various royal and noble residences. To the west, blocks arranged around inner courtyards were designed in a contemporary style. Although Karl Friedrich Schinkel designed many of these buildings, his role of urban planner was reserved exclusively for the Lustgarten and Friedrichswerder.

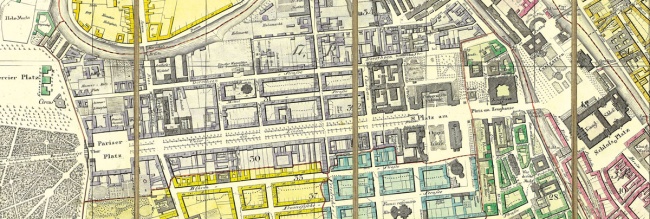

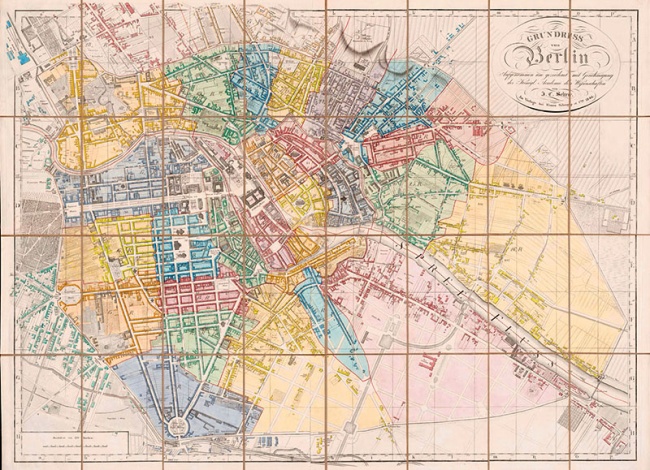

Map of Berlin, Jean Chretien Selter, 1846

The development of Berlin throughout the 18th and 19th centuries is documented in colourful maps that designate the regions, districts and neighbourhoods of the city. The 1846 “Selter Map” outlines the Schinkel and early post-Schinkel period. Unter den Linden is clearly distinguished from all other streets.

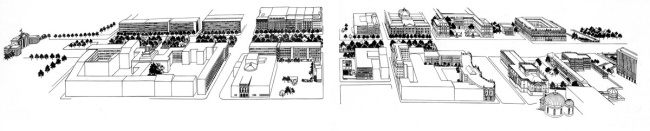

Panorama of Unter den Linden, 1841

This panorama, known as the “Lindenrolle”, was created at the start of Schinkel’s career in 1820 by an unknown artist. It outlines the entire perimeter development with reasonable accuracy and remains an important document of the city’s history.

Unter den Linden, Waltraut Volk, 1971

Inspired by the earlier “Lindenrolle”, Waltraut Volk, the heritage conservationist and art historian, commissioned a panorama of Unter den Linden. It details the precise state of buildings as they stood around 1970. This is now a valuable document charting the demolition and building projects of the north-western sections during the GDR era.

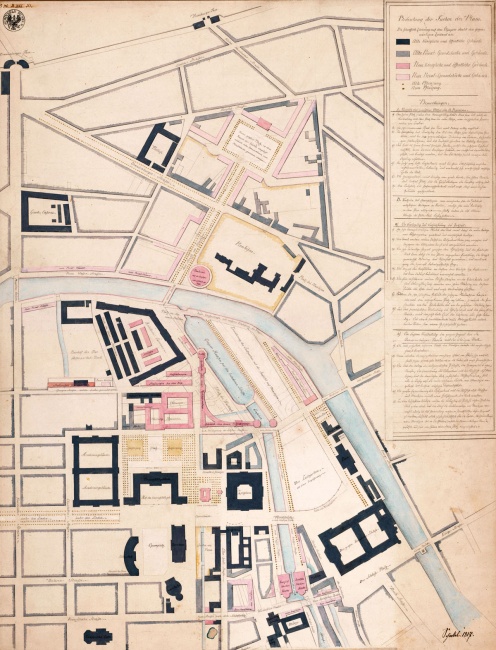

Plan by Karl Friedrich Schinkel for the centre of Berlin, 1817

Schinkel’s design for the Neue Wache was his first foray into urban planning. This included the development of Friedrichswerder, areas north of Oranienburger Strasse, the Lustgarten and the entire area of the “Kupfergrabenlandschaft”.

View facing the Tiergarten outside Berlin, Johann Stridbeck, 1691

This illustrates the four rows of lime trees running along a central course on Unter den Linden. The trees have already grown to a considerable height. Opposite the southern palaces and residences, are the Königliche Stallgebäude (Royal Stables) which were later demolished to make way for the Academy of Fine Arts.

Berlin in 1688, Johann Bernhard Schultz

This bird’s eye view of Berlin illustrates the city’s heavy fortifications including the densely built-up fortress and the Dorotheenstadt district. The fortifications carry as far as Potsdamer Tor, though the avenue that would become Unter den Linden is already marked out as a distinctive “park land”.

The History of Berlin through a Magnifying Glass

No other place in Berlin is as symbolically charged as that of Pariser Platz, home to the Brandenburg Gate. The avenue Unter den Linden, which begins here and was once elevated as via triumphalis, has remained a constant feature despite turbulent times. Napoleon’s army marched along here in 1806, followed later by the victorious Prussians. The National Socialists celebrated their fateful coming to power here in 1933 and the Red Army led their victory parade along the avenue in 1945. In 1953, East Berliners calling for liberation held their demonstrations here, and it was here that a reunified Berlin celebrated the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9th November 1989.

Emperor Napoleon’s march into Berlin, painting by Charles Meynier

After his victory against Prussia, on 27th October 1806, Napoleon entered Berlin with great pomp and parade. He “kidnapped” the Quadriga statue from the Brandenburg Gate and brought it to Paris. Its return to Berlin was equally triumphant when in 1814 it was restored atop the Gate and enriched by

Schinkel’s Iron Cross in the Victory Wreath. The formerly known “Quarree” was then renamed Pariser Platz.

Emperor Wilhelm II with his six sons on Schlossbrücke bridge, 1913

Crowds would gather annually in eager anticipation to see Emperor Wilhelm II and his sons participate in the changing of the guard ceremonial parade at the Zeughaus. It was traditional for the Hohenzollern royal family to assign regiments to their descendants and to present them in full military dress at public events.

A Spartacus League demonstration, 8th December 1818

After their defeat in the First World War, sailors from the Imperial Navy in Kiel mutinied. The uprising, which spread widely throughout Germany and even reached the Imperial capital, was quickly crushed. The main fighting and protests were concentrated at the Brandenburg Gate, along Unter den Linden and at the Lustgarten.

National Socialist torchlight procession through the Brandenburg Gate, summer 1933

The National Socialists utilised the power of place and symbolism. They recreated their 1933 “victory celebration” for a propaganda film, featuring a bombastic torchlight procession. Not long after, the books of dissident authors were burnt at Opernplatz.

The destruction of Unter den Linden during the Second World War

Between 1943 and 1945, Unter den Linden was subject to intense bombardment that destroyed many of its buildings, especially after the “Battle for Berlin”. Almost all the buildings that had bordered Pariser Platz were reduced to rubble. The Brandenburg Gate was the only structure to survive the

inferno of National Socialism.

Demonstration at the Brandenburg Gate, 17th June 1953

After 1945, Berlin was divided into various sections by the occupying powers. This precipitated the later division between East and West Berlin during the Cold War. This uprising against the GDR East German government on 17th June 1953 was only suppressed once Soviet troops were brought in.

Unter den Linden in the shadow of the Berlin Wall, August 1967

When the Wall was built 13th August 1961, the solitary Brandenburg Gate was obstructed and made inaccessible to both sides. Pariser Platz, empty without its buildings, was also impassable. The shots fired at the Wall claimed the lives of 169 people.

The fall of the Wall, 9th November 1989

The Wall was toppled by a “peaceful revolution” brought about by the people of the GDR. Footage of young people on top of the Wall at the Brandenburg Gate was seen all around the world. This was followed in the 1990s by rule-governed redevelopment around Pariser Platz.

Key Figures

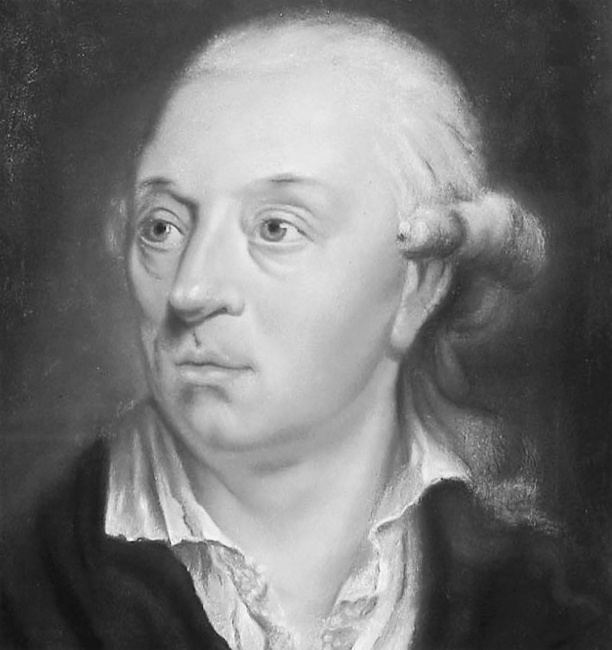

Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1780–1841)

The Prussian architect shaped pre-industrial Berlin like no other, especially along Unter den Linden. Schinkel was a civil architect, head of the Prussian building administration and architect to the King. He was an early member of the Architekten-Verein and gave his name to what is still the most important German competition for young building professionals.

Carl Gotthard Langhans (1732–1808)

The architect created his most famous building – the Brandenburg Gate, Berlin‘s landmark and national symbol – while working in the high Prussian civil service. The road linking Berlin with the city of Brandenburg an der Havel lent the gate its name. Langhans designed other important Berlin buildings, such as for Schlosspark Charlottenburg.

August Stüler (1801–1865)

The co-founder of the Architekten-Verein was extremely productive both at home and abroad, building hundreds of churches as head of Prussian cultural buildings and succeeding Karl Friedrich Schinkel as “architect to the king”. His main works in Berlin include the innovative Neues Museum, the palace dome and the „Summer Houses“ on both sides of the Brandenburg Gate.

Heinrich Strack (1805–1880)

Even as a student at the Berlin Building Academy, the future imperial architect was one of the founders of the Architekten-Verein. This was followed by a wealth of work for the royal family, including the remodelling of the Kronprinzenpalais and Babelsberg Palace near Potsdam. Major works in Berlin include the National Gallery on Museum Island, the Victory Column (today on the Großer Stern in the Großer Tiergarten) and the – now destroyed – St Peter‘s Church on Spree Island.