Swinemünder Straße

Hobrecht’s Berlin

Most of the buildings in central Berlin are a uniform height, standing at 22 metres. Until the First World War, this equated to five storeys high. In suburban

areas, buildings were four storeys. Today, these two kinds of stucco-decorated apartment blocks are characteristic of Berlin. The buildings are constructed around central courtyards, hidden from the street. It is also characteristic that most of the city centre streets are 22 metres wide with generous pavements. This particular measurement – 22 metres – is the Berlin dimension par excellence, creating a feature that is unique throughout Europe. This stems from regulations devised by architectural engineer James Hobrecht, who drew up the “Development Plan for Berlin and its Surroundings” for the Prussian Minister of the Interior in 1862. Hobrecht later became a city planner for roads and bridges, and long-term chairman of the Architekten-Verein zu Berlin. There, he not only designed the street system that still characterises central Berlin today, but also pioneered a significant sewage system that served as a model for other cities around the world. Swinemünder Strasse is one of the important streets within the 1862 development plan.

Swinemünder Strasse with the Millionenbrücke bridge, 1908

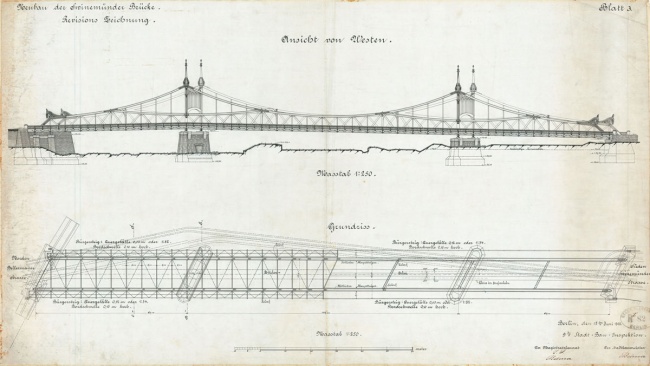

Berlin’s longest and most expensive bridge of the time was designed by Art Nouveau architect Bruno Möhring and engineer Friedrich Krause. Begun in 1905, it restored Swinemünder Strasse to its original length after it had been interrupted in 1871 by the Ringbahn Railway.

Three Squares

Swinemünder Strasse together with the sequence of squares at Zionskirchplatz, Arkonaplatz and Vinetaplatz were cornerstones of the “Development Plan for Berlin and its Surroundings”. The development begins in Mitte, at Zionskirchplatz, and extends northwards for almost two kilometres towards Gesundbrunnen. Both the church and the square at Zionskirche church were designed by August Orth, one of the most prominent church architects at the time. Arkonaplatz and Vinetaplatz were conceived as decorative plazas by Hermann Mächtig, who held the position as the city’s landscape architect, the head of the city parks administration.

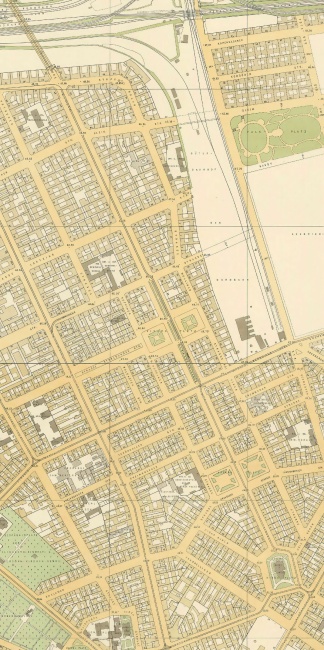

Detail from the Straube plan showing the route of Swinemünder Strasse, 1910

The 1,900 metre-long Swinemünder Strasse connects Zionskirchplatz with Swinemünde Bridge. Until the Second World War, a tram ran along the wide central promenade.

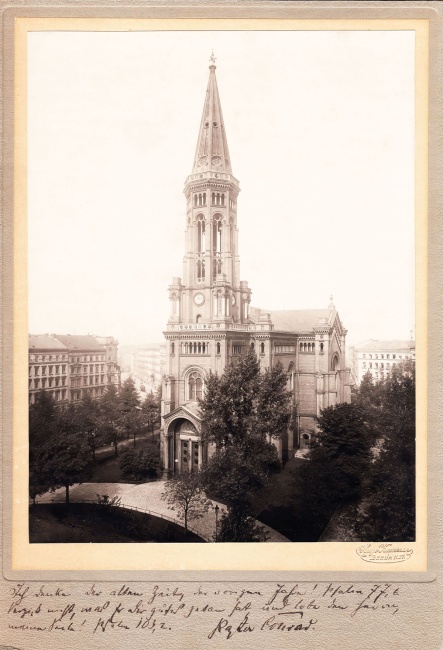

Zionskirche and Zionskirchplatz bordered by apartment buildings, around 1900

The church and square were designed by August Orth, from plans by Gustav Möller. The architects’ primary focus was the design of the surrounding gardens. As a result the church is unusual, as it is not built pointing eastwards, which is the customary orientation.

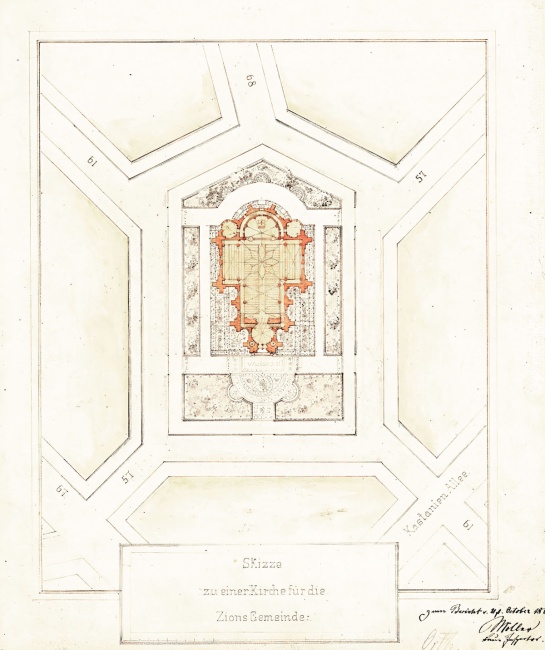

Zionskirchplatz with the layout of Zionskirche, 1866

August Orth designed the pentagonal square in line with Hobrecht’s plan, including a grand semi circular forecourt, tiled pathways, with tree lined flowerbeds and latticework borders.

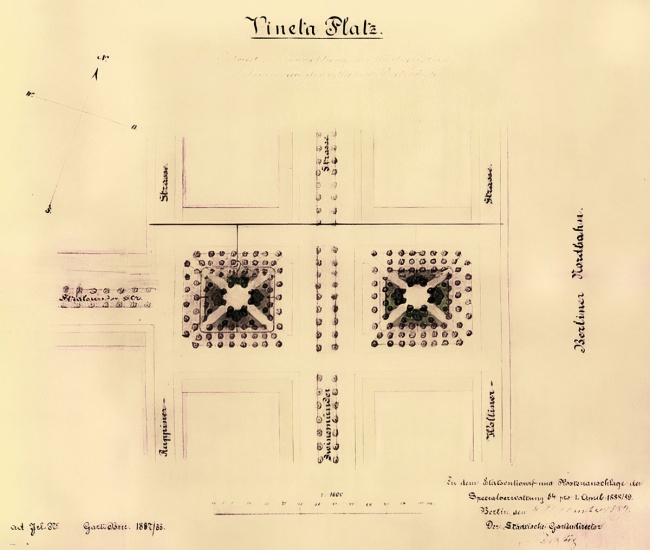

Design for Vinetaplatz, 1887

Berlin’s director of public gardens, Hermann Mächtig, designed two symmetrical squares which – in line with the contemporary fashion – included diagonal paths and trees planted symmetrically. The plan was first drawn up by James Hobrecht.

The Street and the Berlin Apartment Block

Hobrecht’s vision for the city involved dividing the street system between wide avenues and narrower residential roads. The main streets were constructed by the city authorities to a high standard, while the residential blocks were subdivided into narrow plots and sold off to private developers. The design and construction of the apartment buildings was left to the landlords and their architects, so long as they adhered to building regulations. This is why Berlin is made up of more or less uniform streets that house apartment buildings with subtle variations on a theme.

View from Zionskirchplatz north into Swinemünder Strasse, around 1870

Foregrounded is the fine latticework bordering at Zionskirchplatz, and in the background is Swinemünde Bridge.

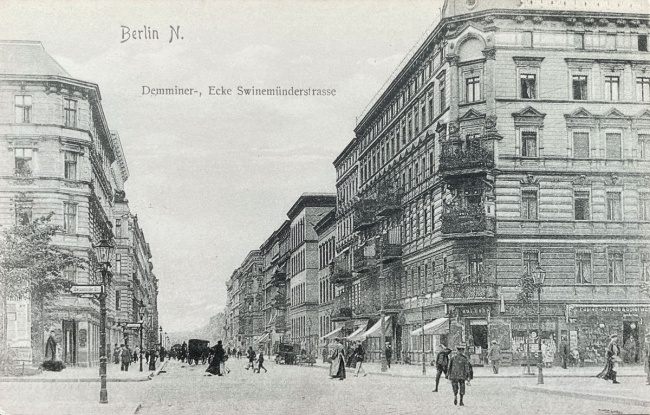

Swinemünder Strasse looking west towards Demminer Strasse, around 1910

Between Bernauer Strasse and Demminer Strasse lay the spacious heart of the Brunnenviertel neighbourhood with its generous central promenade and restaurant terraces.

View of Swinemünder Strasse looking north across Bernauer Strasse, around 1920

The tram line was relocated to the centre of the promenade to accommodate increasing traffic in the adjacent lanes.

Swinemünder Strasse at the corner of Rügener Strasse with a view of the Swinemünde Bridge, around 1930

When the Swinemünde Bridge was built, it connected the Brunnenviertel with Gesundbrunnen, north of the Ringbahn railway line.

The subdivided street, 1896

The official map of Swinemünder Strasse shows the numbered plots and names of the various owners. Most apartment buildings were owned by one person, but in some places, entire sections of the street would belong to a single person.

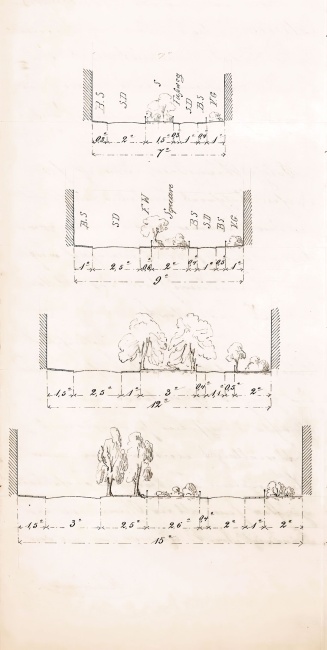

Street sections and their landscaping, 1861

This page, taken from James Hobrecht’s report on section X of the development plan, shows street sections of different widths and configurations; tree planting, pathways, flowerbeds, and front gardens.

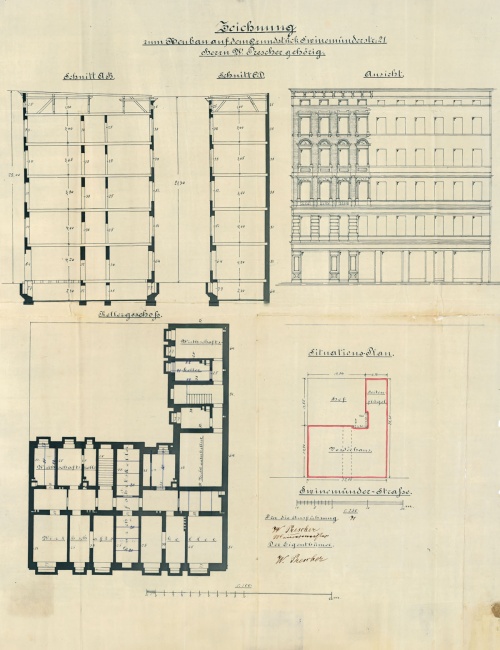

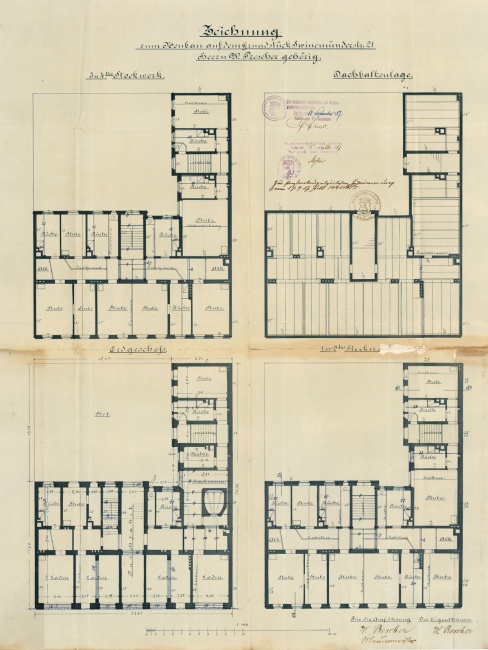

Construction of a Berlin apartment building at 21 Swinemünder Strasse, 1887

A planning application for an apartment building with a front building and attached side wing submitted by a master builder named Prescher, who is listed as both owner and contractor.

City Engineering

James Hobrecht’s development plan also involved the introduction of state-of-the-art infrastructure. As a means of improving public health and transport for the growing population, a huge bridge-building programme was put into effect. This was alongside new transportation systems for; drinking water, gas, electricity, and sewage. Without this carefully orchestrated city engineering, Berlin would not have become the metropolis of today.

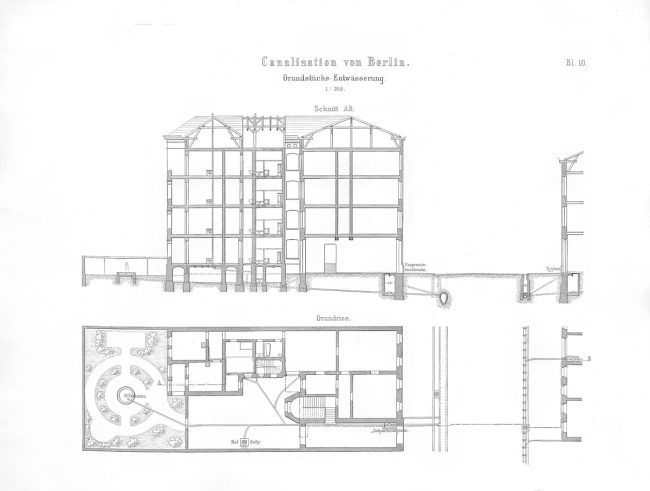

James Hobrecht, schematic diagram of road and property drainage, 1884

Hobrecht’s Berlin drainage system collects runoff from streets, courtyards, and individual households into a central sewer. It is then channelled via pumping stations to several large treatment plants outside the city.

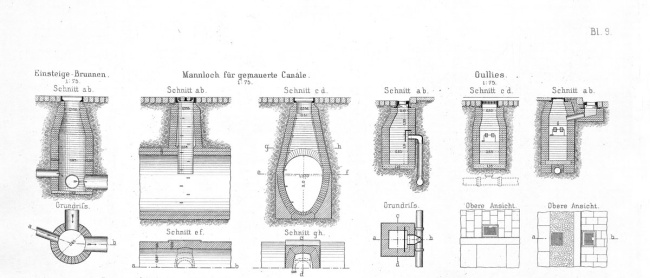

James Hobrecht and the elements of urban drainage

This underground sewage system was seen at street level in the paved gutters, granite kerbs, cast-iron inlets and manhole covers. Even today, these details will indicate if you stand in an area improved by Hobrecht’s sewage system.

Swinemünde Bridge, 1906 complete overview and drawing

The immense bridge-building programme conducted during the imperial era helped to improve connections between areas of the growing metropolis. Projects such as the Swinemünde Bridge, designed by architect Bruno Möhring and engineer Friedrich Krause, also symbolised the dawn of the modern era.

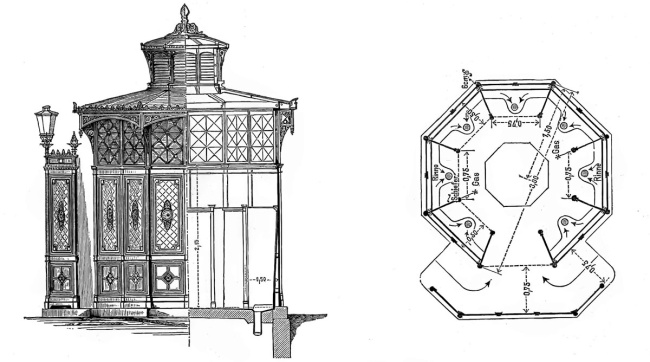

Berlin’s gas street lamps

Gas street lamps were an integral part of Hobrecht’s modernisation plan for Berlin. Beautiful lamps brightened the streets and increased public safety, which markedly improved living standards across the city.

Elevation of a public toilet block, 1878

Popularly known as the “Café Achteck” (Café Octagon), these green-painted, ornamentally decorated cast-iron urinals were part of a large-scale programme to ensure sanitary public spaces and modernise the city.

The Grand Plan Still Standing

Around the year 1860, Vienna, Barcelona and Paris were modernising alongside Berlin. The 1862 “Development Plan for Berlin and its Surroundings” meant the Prussian capital became a formal part of this pan-European evolution. The plans were the brainchild of the state, not the individual cities. Whilst drawing up the plan, James Hobrecht would work in his “Commissarium” at the Royal Police Headquarters, liaising closely with landowners to incorporate existing streets and buildings into the framework. However, the mounting costs did stop numerous neighbourhood squares and residential streets from being realised.

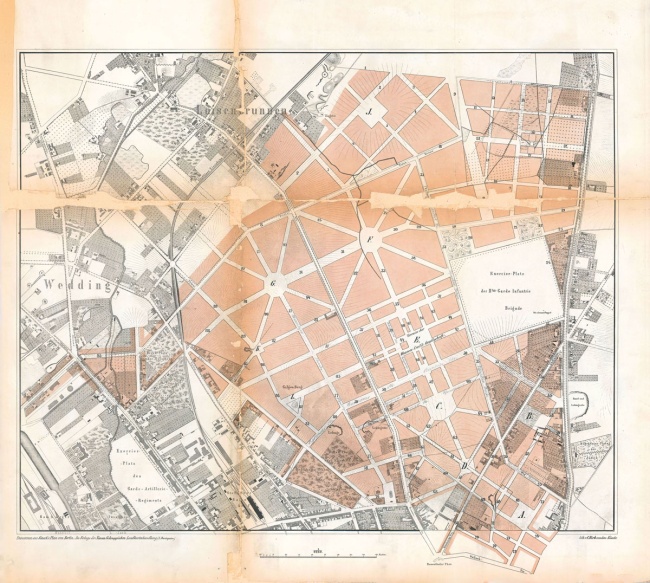

James Hobrecht, Variant A, Section XI of the City Expansion Plan, 1861

Hobrecht devised numerous options for the squares along Swinemünder Strasse. However, these were not realised due to objections raised by property owners, the magistrate and the city council as well as the construction of the Ringbahn rail network.

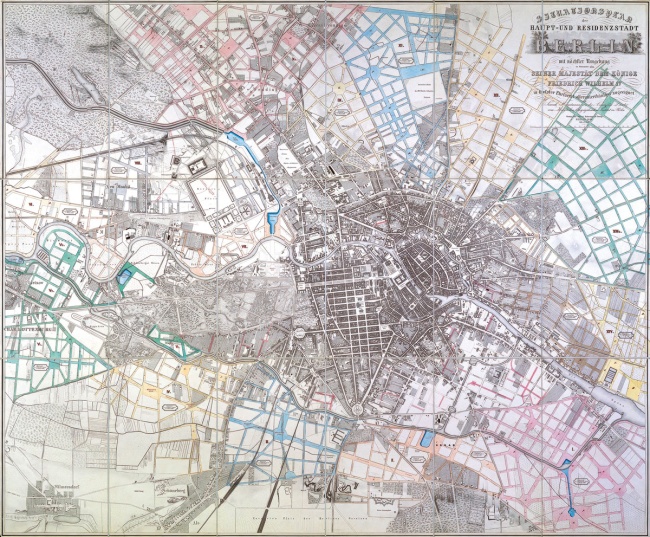

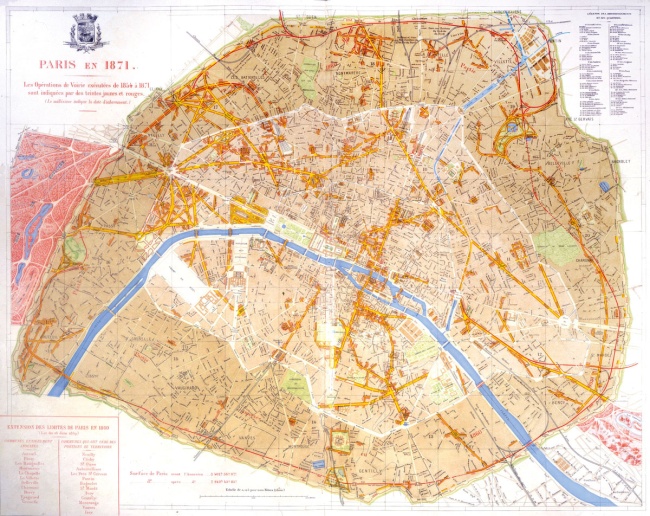

Plan of Berlin and its surroundings as far as Charlottenburg by James Hobrecht, 1862

The 15 sections of the development plan are shown here. According to Hobrecht’s calculations, the 50-year plan was designed to accommodate one and a half million additional inhabitants.

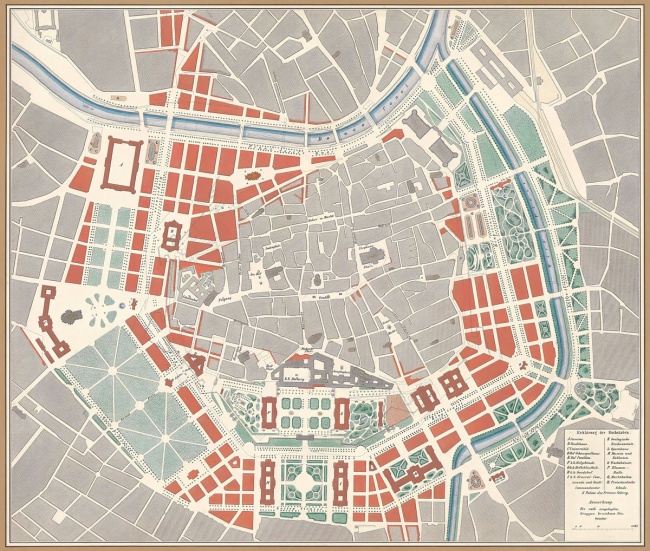

The unrealised streets and squares of the Hobrecht plan

Mostly as an economising measure, the streets highlighted in red were not built. This resulted in the construction of fewer squares and the creation of larger blocks than planned.

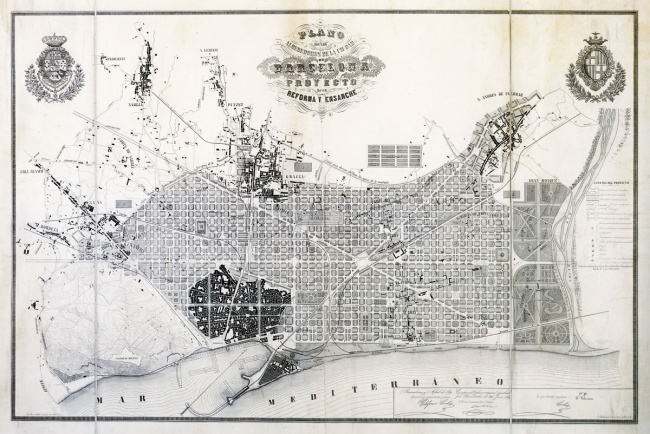

City expansion plans for inner city Vienna from 1859, for Barcelona from 1859 and for the remodelling of Paris from 1853

Whilst Hobrecht and the committee were devising a plan for Berlin from 1859, other major European cities were planning equally large scale developments.

The Division of Urban Regeneration in West and East

When the Berlin wall was erected in 1961 at Bernauer Strasse, it split Swinemünder Strasse in two. As the road had an end in both the East and the West, it became a prime example of the differing regeneration styles. On the West side, the “Wedding/Brunnenstrasse redevelopment project” consisted of entirely new buildings, whereas across the Wall, historic houses would remain as they were until 1971 when the government rebuilt them as part of a landmark homebuilding policy.

The “Wall of shame”, pictured in July 1963

After the Wall was first built in 1961, bricks were replaced by fortified concrete as shown here in 1963 at the corner of Bernauer Strasse and Swinemünder Strasse. The walled-in buildings at 21 to 24 Swinemünder Strasse were demolished around 1966 to expand the order facility, on the left.

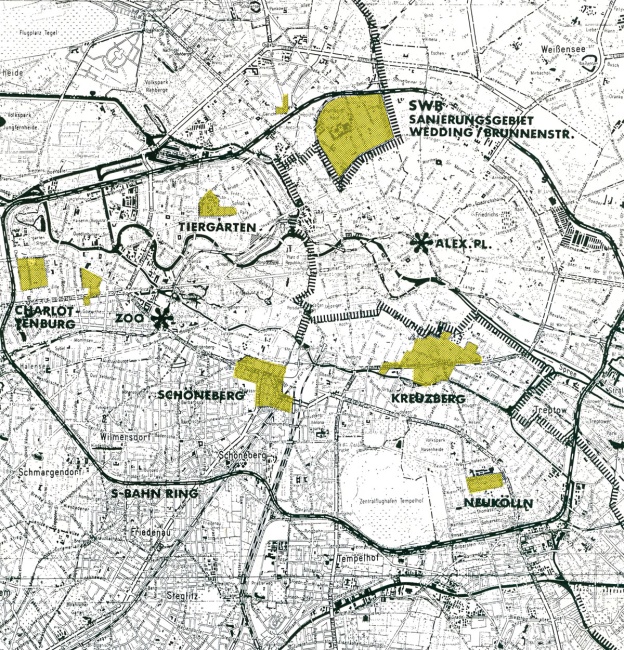

Designation of the areas set for the first urban renewal programme, 1963

The “Wedding/Brunnenstrasse redevelopment project” was one of seven regeneration plans for Berlin, the largest in Germany and supposedly even the largest in Europe. This meant the total levelling of all existing buildings on the northern part of Swinemünder Strasse along from Bernauer Strasse. The West Berlin Senate was convinced that this would help to create a better city.

The beginning of the demolition at the corner of Swinemünder Strasse and Demminer Strasse, 1963

The extensive demolition process began once the old buildings had been vacated.

Demolition work around Vinetaplatz, around 1949

This image contrasts the Stralsunder Strasse which had been completely levelled with Vinetaplatz behind, its remaining old buildings set for demolition.

The first new buildings of the “Wedding/Brunnenstrasse redevelopment project”

The first completed residential buildings on Usedomer Strasse are proudly advertised here in a 1964 Senate brochure.

Reconstruction of an old building in the Arkonaplatz redevelopment project, 1974

This reconstruction project was planned in the East Berlin district of Mitte, directly south of the Wall. From 1970, artisanal craftsmen were brought in to carefully renovate the old buildings. The “Horst Kunze Brigade” is proudly posing in front of one of their finished projects.

The reconstruction of old buildings in Zionskirchstrasse, part of the Arkonaplatz redevelopment area, 1984

The redevelopment area stretched from Rheinsberger Strasse in the north to Zionskirchplatz in the south and included the blocks around Arkonaplatz, here with a view from Zionskirchstrasse into Griebenowstrasse.

Renovation of a building interior as part of the Arkonaplatz redevelopment project, 1984

During the renovation of the old buildings, some of the rear buildings at the back of the courtyards were demolished. This allowed for more spacious communal courtyards to be built, something that was being done concurrently in West Berlin.

Ceremonial handover of the two millionth flat, 1984

A renovated apartment at 120 Swinemünder Strasse was unveiled “in the presence of Erich Honecker” on 9th February 1984, celebrating an important milestone in the SED’s 1971 housing project that promised up to three million new and modernised apartments for East Berlin.

Key Figures

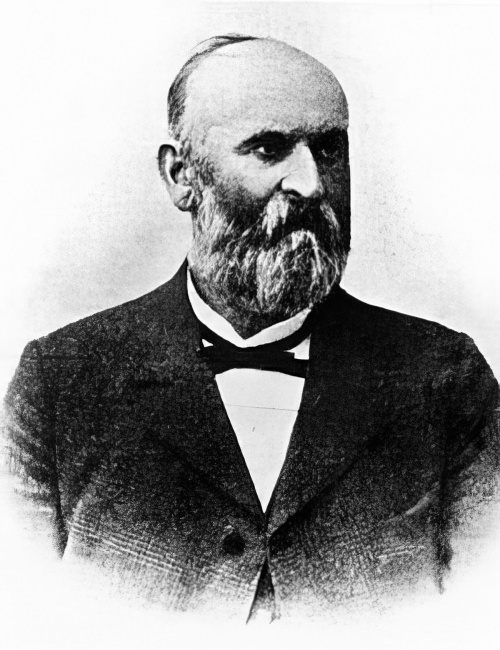

James Friedrich Ludolf Hobrecht (1825–1902)

Having successfully passed civil engineering examinations for water, road and rail design at the Bauakademie, Hobrecht went on to draw up the “Development Plan for Berlin and its Surroundings” on behalf of the Prussian state in 1859. In 1873, he became the chief engineer behind the construction of Berlin’s sewage system and by 1885 was Berlin’s city planning commissioner for civil engineering. Barring a short pause, he was chairman of the Architekten-Verein zu Berlin between 1873 and 1887.

August Orth (1828–1901)

After graduating from the Berliner Bauakademie, Orth went on to work for various railway companies, before becoming a freelance architect in 1866. As the visionary behind the Berlin city railway and numerous stations and churches, Orth made a lasting impact on the Berlin cityscape. Orth was a member of the Architekten-Verein zu Berlin from 1852, before becoming a board member in 1872 until 1877.

Hermann Mächtig (1837–1909)

After training under Peter Joseph Lenné and Gustav Meyer, in 1877 Mächtig succeeded Meyer as the Berlin director of landscape architecture, remaining in post until 1909. During 30 years in office he designed many of Berlin’s parks, squares, and streets, such as Viktoriapark, Vinetaplatz, and Schloßstrasse in Charlottenburg.

Friedrich Krause (1856–1925)

Krause studied at the Berliner Bauakademie before working as a city planning officer in Stettin. In 1897 he succeeded James Hobrecht as Berlin’s city planning commissioner for civil engineering. While in post, he played a key role in improving transport infrastructure, for example with the building of the eastern and western docks and the construction of numerous bridges. He was an honorary member of the Architekten-Verein zu Berlin.