Schloßstraße in Steglitz

After 1990: Slowing Traffic?

The fall of the Berlin Wall was accompanied by a surge in motor traffic, but also increased public frustration at the measures adopted to make the city more car friendly. To meet the demands of increased traffic, the ring road motorway was extended, but little else was done to accommodate the influx of cars. That being said, work was done to separate the different kinds of traffic, but was planned with little foresight or reflection after completion. For example, attempts were made to convert the car-heavy Schloßstrasse Steglitz, nestled between Walther-Schreiber-Platz and the nameless square south-west of the Steglitz roundabout. By 2011 the work was complete, featuring new cycle paths and single lanes for cars in both directions running parallel to the A 103 motorway. The resulting changes saw department stores mutate into larger shopping malls, a small cultural hub emerge around the historic manor house and seemingly endless renovation work to the Steglitz roundabout.

Schloßstrasse Steglitz today

Its smooth green cycle paths have been a familiar feature since 2021. In the background is the high-rise tower of the Steglitz roundabout, a prominent but controversial landmark. Various district authorities were located there until 2007, but since then it has been vacant.

Dismay: Loss of Spaces

The tram tracks were removed in 1963, after which Schloßstrasse was widened to become a section of the B1 road with three lanes of traffic moving in each direction. Once the A 103 motorway was opened in 1968, Schloßstrasse, originally designed as a shopping street, was no longer a thoroughfare. However, the squares along the stretch were not designed for pedestrians; Walther-Schreiber-Platz, Franz-Amrehn-Platz at the “Bierpinsel”, Hermann-Ehlers-Platz, and the vast square to the south-west of the Steglitz roundabout remained an unsolved problem.

The remnants of Walther-Schreiber-Platz featuring the Schloss-Straßen-Center and medical centre

This area was created in the 1950s by setting the buildings back from the road and building a new clothing store (now a medical centre) and a department store. After the Schloss-Straßen-Center (on the left in the picture) was built, the square was destroyed, and a new area was created in front of Forum Steglitz.

The square to the south-west of the Steglitz roundabout with its old manor house

The picture shows one of the most unsightly squares in Berlin, a place with no distinct name. Here, the A 103 motorway ends and meets Schloßstrasse, which bends to the south-west. Cars are funnelled in the various directions of the city’s road network, taking up an inordinate amount of space.

Franz-Amrehn-Platz and the “Bierpinsel”

Despite the square being visible from the Joachim Tiburtius Bridge, it is nearly impossible to access. The modestly proportioned and uninviting area between the department stores, underground station and overpass bears no resemblance to its former life as the splendid Schildhornplatz.

Hermann-Ehlers-Platz with its town hall, Steglitz roundabout and the A 103 motorway

Hermann-Ehlers-Platz lost its distinctive triangular layout after demolition works were done to incorporate the A 103 motorway and the building of the Steglitz roundabout’s out of proportion foundations. Since Albrechtstrasse and Grunewaldstrasse were connected, the square has been reduced to a veritable wasteland.

Powering into the New Consumer Society

A reduction in car traffic boosted the retail economy of Schloßstrasse as specialist shops, department stores, and shopping malls began to attract more customers. However, problems arose from the lack of quality public space and the narrow pavements. In an effort to improve things, since 2010 the road has featured a green central reservation and widened pavements lined with trees. Despite these measures, this once booming shopping district is now dwindling. Perhaps Schloßstrasse needs reinventing.

Unveiled in 2006: “Das Schloss”

The historic Steglitz town hall (to the left of the picture) looks modest in comparison to the first large shopping centre built in the newly reunified Berlin, which is almost two football pitches in size. An elaborate advertising campaign accompanied the launch of “Das Schloss”, which still attracts plenty of visitors today.

Forum Steglitz and Schloss-Straßen-Center under construction, 2006

The first shopping centre to open on Schloßstrasse (Forum Steglitz, opening in 1970, pictured on the left) has been redeveloped several times. It remains to be seen whether the Schloss-Straßen-Center (pictured centre) will meet a similar fate given an insolvency administrator was appointed on 1st March 2024.

Boulevard Berlin, opened 2012

There used to be two neighbouring department stores on Schloßstrasse: Wertheim and Karstadt. In 2010 Boulevard Berlin – a vast shopping mall – was built on the Wertheim site. The street connection between the sites was replaced by a glass walkway joining it to the Karstadt store.

Galleria at 101 Schloßstrasse, opened 1995

With its oversized window displays Galleria – the first shopping arcade built after reunification – offered a shop-in-shop experience. Larger scale shopping centres cropped up along Schloßstrasse after the opening of Galleria, though all with a design similar to the original.

Culture – More Than Just a Souvenir

In the early morning, the shadow of the Steglitz Kreisel tower travels over the cemetery of St Matthew’s Church, casting the Spieß family memorial into shade. The Spieß family owned the village of Steglitz for nearly 200 years between 1517 and 1713. Every passing generation leaves its mark on a place and every era an influence. It is a sensitive task to preserve these relics of place for future generations and not every attempt is successful. “Culture is the wealth of problems”, as Egon Friedell mocked.

Shining as bright as opening night: the former Titania-Palast

The Titania-Palast cinema opened its doors for the first time in 1928 to 1,900 visitors with a series of spectacular screenings making it an instant attraction. After the war, the Freie University (FU) was founded there. In the 1960s, the theatres were closed to make way for shops. However today, CINEPLEX-Titania houses seven movie theatres and a total of 1,200 seats.

An uncertain future: „Bierpinsel“, without the beer

This well-known 1970s architectural icon has been abandoned for some time. Its street art covered façade recalls the failed attempt to open a “tower of the arts” in 2010, featuring seminars, workshops, and an art café. The nearby overpass continues to hinder the future of the building.

The Progrom Night memorial wall on Hermann-Ehlers Platz

The synagogue housed in the courtyard of Wolfenstein House was vandalised during Progrom Night in 1938. This reflecting wall of mirrors was erected to commemorate the 9th November 1938 and the deportation of 1,758 Jewish citizens, their names engraved on the panes. The wall stretches along the entire site of the former synagogue.

The Schwartz Villa brought back to life

The Schwartz Villa was built in 1895/96 as a summer house for the banker Carl Schwartz. It fell into disrepair during the division of Berlin and was scheduled for demolition by the West Berlin authorities. After public protests, the state of Berlin opted to transform it into a cultural centre, which opened in 1995. It now hosts concerts, exhibitions, lectures and a popular café.

The Steglitz manor house, restored in 1995, is a lasting remnant of old Steglitz

The manor house was built at the beginning of the 19th century in the style of early Prussian classicism and was home to many prominent figures of the day. Its grand presence gave Schloßstrasse its name, with “Schloß” meaning “castle” in German. Today, the large hall is available for private hire.

A popular favourite: the Schlosspark theatre

This small theatre, its director and company, rose to prominence in the 1950s. Today, it is known to audiences far and wide and runs a full programme of entertainment thanks to Dieter Jürgen “Didi” Hallervorden.

The Great Cost of Less Traffic

The Schloßstrasse shopping mile was designed to improve the quality of life of its surrounding residents. A part of this plan was to reduce the volume of traffic along the thoroughfare. Reducing traffic was one thing but perhaps it was too late. The adjacent roads house thousands of empty parking spaces at street level, not to mention the numerous multi-storey car parks. Including the spaces under the overpass, there are around 4,500 parking spaces in the immediate vicinity of Schloßstrasse. These sterile urban deserts are not particularly inviting.

The square without a name

To the left of the image is the eponymous manor house to which Schloßstrasse owes its name. The entrance to the shopping mile is marked by the multi-storey car park and an open expanse of tarmac. In the background are the three towers of St Matthew’s Church, the town hall and the disused office block at Steglitz roundabout.

The half finished motorway junction

In 1970, in preparation for the merging of two motorways, an 800-metre-long bridge was built across Schloßstrasse, the railway lines, and the A 103 with access ramps. Car parks were created under the bypass, some with multiple levels.

Joachim Tiburtius bridge and the “Bierpinsel”

The bridge was built to hold the A 104 motorway and has four lanes for traffic and two hard shoulders. These plans were cancelled in the 1970s meaning the A 104 never reached the Bierpinsel, and the hard shoulders are now used for car parking.

Gloomy entrance to the “Bierpinsel” under the Joachim Tiburtius Bridge

The entrance to the tower’s restaurant is gloomy and uninviting, in the shadow of the enormous bridge designed for a four-lane motorway. The bridge, as well as the Bierpinsel and the two underground stations below are now heritage-listed.

No place to live: multi-storey car park on Schildhornstrasse

The remaining old buildings on Schildhornstrasse can be seen on the left of the picture. Public protests in the early 1970s prevented construction of a major road and therefore further demolition work. A roadside sales pavilion remains in place with its excessively wide garage access, large enough to accommodate the six lanes of adjacent traffic.

Public space at the intersection of Schloßstrasse and the motorway bridge

The Senate has announced a plan to improve the quality of public spaces by reducing the amount of concrete and adding greenery and landscaping. However, this will be simply impossible unless the oppressive architecture designed for the “city of cars” is also dismantled.

Growing from a Village into the City

When Steglitz was still a village it was prominently located along the connecting route between the royal residences at Potsdam and Berlin. Later, it was joined to the Reichsstrasse 1, a road flanked by the first railway line of the Prussian Kingdom. Steglitz was the largest rural municipality in Prussia following the First World War, boasting a population of over 80,000, and in 1920 it was absorbed into the newly formed Greater Berlin. Alt-Steglitz survived until the 1960s until it was flattened and replaced with the Steglitz roundabout. It is the only historic village absorbed by Berlin that bears no trace in the city today.

Schloßstrasse pictured with a tram passing in front of Steglitz town hall, around 1900

The Western Berlin Suburban Railway Company (founded in 1895) took over a fleet of wagons belonging to the Berlin Steam Tramway Consortium, and converted the carriages to run on electricity. All tram lines in Berlin were electrified by 10th August 1900. The tram tracks ran between the road and pavement.

The splendid Schildhornplatz, 1905

Until around 1930, at the junction of Schildhornstrasse and Schloßstrasse, there was a pretty, triangular shaped square that housed a memorial. As preparations for the motorway began, Schildhornstrasse became collateral damage and the square was demolished, the buildings on the left levelled and the road widened from 26 to 62 metres.

On top of the store: Berlin seems dreamlike, 1952

Berlin’s first new department store after the Second World War opened as a Wertheim, on Schloßstrasse. It was completed with a novel feature in the form of a rooftop restaurant. The public enjoyed this new perspective on the street below and across the adjacent rooftops. The façade is still intact and is a protected feature.

Buses, trams, and cars: traffic on Schloßstrasse, 1955

Schloßstrasse after its transformation, with pavements reduced to 3.5 metres and no longer the tree-lined avenue of yesteryear. Overhead electric cables run down the middle of the road, powering the trams and trolleys, while the first diesel double-decker buses trundle down the lanes. Schloßstrasse has become a destination in itself, West Berlin’s shopping strip.

Now forgotten: the Bornmarkt in 1968

There was a weekly market that operated for over 60 years on the undeveloped land between Friedenau and Steglitz. From 1908, farmers brought their produce for sale, and permanent stalls were constructed to accommodate their trade. Forum Steglitz, Berlin’s first shopping centre opened here in 1970, and on the right rises the Titania-Palast theatre.

The “Bierpinsel”: the colourful 1970s

Ralf Schüler and Ursulina Schüler-Witte were tasked with designing a connection hub for the underground railway. They drew up their vision of an aerial fruit-like structure. Built between 1968 and 1976, the Bierpinsel and its tower restaurant became prominent Berlin landmarks.

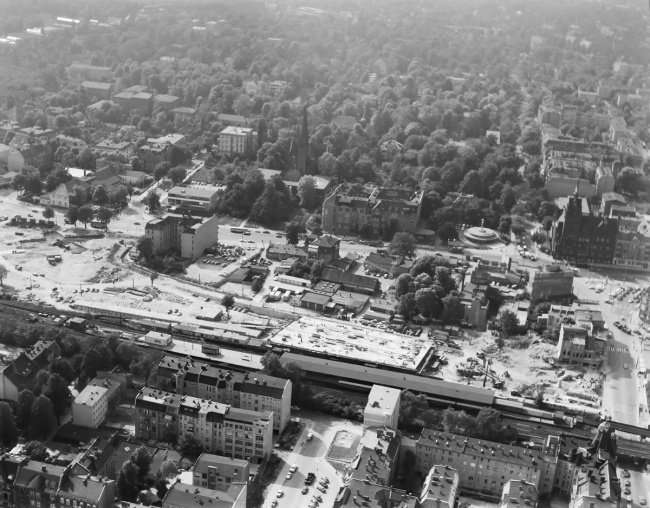

The Steglitz village is no more, 1970

By the time of this photograph, Steglitz town centre and its railway station had already been demolished to make way for the A 103 slip road. The rest of the village was later torn down to accommodate the Steglitz roundabout.

The construction of the Steglitz roundabout by the A 103 motorway, 1972

This tower block, designed by Sigrid Kressmann-Zschach, was completed in 1972, but remained empty for years after. In 1977 the local council became a tenant before the state of Berlin took control of the controversial building in 1988. The building of the A 103 motorway meant the B1 no longer had to run along Schloßstrasse.

Key Figures

Günther Drobisch

Günther Drobisch was responsible for redesigning Schloßstrasse whilst he was the Steglitz district planning officer between 2008/09. He widened the pavements, planted new trees and improved the cycling infrastructure, all of which had a significant impact on the quality of life for residents.

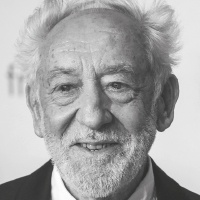

Dieter Jürgen „Didi“ Hallervorden (geb. 1935)

“Didi” has been known throughout Germany since the 1970s, as a character played by actor and cabaret artist Dieter Jürgen Hallervorden. In 2008, his company Halliwood Film GmbH has rented the Schlosspark theatre from the state of Berlin. Didi continues to feature in many of their productions.

Manfred Pechtold

Pechtold’s architecture studio designed Berlin’s largest shopping centre which opened in 1994 by converting the shopping arcade in Gropiusstadt. The “Schloss” in Steglitz is arguably the most popular mall designed by Pechtold’s firm, which has designed approximately 270,000 square metres of retail space. Pechtold is a member of the Architekten- und Ingenieurverein zu Berlin-Brandenburg (AIV).

Christoph Gröner (geb. 1968)

Entrepreneur Christoph Gröner’s CG Group acquired the tower block at Steglitz roundabout in 2017. The plan was to develop 330 luxury apartments on its office floors. In 2020, the Adler Group took over the CG Group and all its projects. This project has since stalled.