Wilmersdorf: A 104

Patzschke Architekten

City Instead of Expressway

The place today - a memorial to the car-friendly city

Today the place looks empty and deserted. The ramps of the former motorway have been provisionally cordoned off. Grass is growing out of the cracks in the tarmac. Shards of broken bottles lie in the old tunnel. These are the traces of late-night parties. More or less to the delight of local residents, people are reappropriating the lost urban space in this way.

The viaduct of the A104 motorway is dilapidated and can no longer be repaired. A significant section was already closed in 2023 due to safety deficiencies. The dilapidated ramps must therefore be demolished within the next few years.

As architects, we have been working on the urban space left behind by the former motorway since 2021.

The site is located in the south-west of the city. The area stretches across the districts of Steglitz-Zehlendorf and Wilmersdorf-Charlottenburg. The motorway began at Schlossstraße underground station and ended at the S-Bahn ring road near Hohenzollerndamm.

Southern entrance to the 570 metre long tunnel under the residential complex

© Maximilian Meisse

The first plans for a rapid connection between the middle-class residential areas in the south and the administrative centre on Fehrbelliner Platz further north were drawn up as early as the 1930s. Berlin and Los Angeles have been twin cities since 1967. The bold motorway constructions of the Californian metropolis were seen as the future. Based on this model, the A104 motorway was built in the 1970s and inaugurated in 1980. The motorway cut a swathe through the city.

This was the vision of the car-friendly city. From today's perspective, the seemingly dystopian network of multi-lane motorways appeared excitingly modern at the time. The middle-class city, or what was left of it after the bombing, had hardly any value.

The city was fundamentally changed. The viaduct separated the intact residential areas of Dahlem and Friedenau. The new traffic axis attracted car traffic, which from then on battled its way through the neighbouring residential streets. Under the bridges, gloomy residual spaces were created that still cause unease in some places today.

The project is named after Breitenbachplatz. The square is located on the border between the districts of Steglitz-Zehlendorf and Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf and marks the intersection of several historic street axes. In the south-west, a semi-circle of terraced buildings encloses the square. In the north-east, solitary buildings form the edge of the city. This spatial impression can no longer be experienced today due to the massive buildings of the former motorway. A citizens' initiative has been campaigning for the removal of the ramps for years.

Three structures marked the course of the former A104 motorway, visible from afar: the three chimneys of the Wilmersdorf combined heat and power plant to the north, the ‘Bierpinsel’ on Schlossstraße to the south and the Schlangenbader Straße motorway superstructure or, as the locals say, the ‘snake’ in the middle. The three chimneys of the combined heat and power plant have already been demolished. The ‘Bierpinsel’ is a listed building. However, new safety requirements are preventing this iconic building from being put to good use. The tower with its distinctive mushroom shape is falling into disrepair. The ‘snake’, on the other hand, is still very popular with residents today.

With fourteen storeys and over 1,200 flats, the yellow and white concrete block towers above its surroundings. Most residents enjoy the unobstructed views. But from the outside, the motorway superstructure experiment remains a bizarre one-off in the city. The futuristic shape with the streamlined, bevelled corners of the building bear witness to the utopian thinking of the nineteen-seventies. The architects seem to have modelled themselves on the space stations of science fiction films of the time. Today, the ‘Schlange’ is also a listed building. Nevertheless, it is not suitable as a role model. For most people, the A104 itself and the ‘Schlange’ are a memorial to the destruction of the city.

Today, we are faced with an urban development policy decision: should the car-friendly city be restored with a new motorway costing hundreds of millions of euros or should new, lively urban districts for people be created here? Dismantling the motorway and reclaiming urban space has the potential to be an internationally acclaimed flagship project. We know of projects to convert individual roads, but there are only a few examples of the conversion of an entire motorway. In cities around the world, it began with the appropriation of abandoned industrial, harbour and railway sites. With the mobility turnaround, the overcapacity of private transport is becoming the new issue.

The design - reclaiming the city for living

Our contribution is presented on two levels: Firstly, with the site plan we have developed an urban development proposal for the four-kilometre stretch of the former motorway. On the other hand, we used the visualisation to highlight a specific location along this route as an example.

Level 1 - Site plan for urban regeneration

The site plan shows how the areas freed up after the demolition of the former motorway can be used. A large part of it is to be converted into building land. The buildings shown in red represent the new development. In terms of urban development, we are building on the existing structures. The block structure will be carefully supplemented with a moderate number of storeys. The street space of the former motorway will be reduced to a size that is based on the dimensions of a typical Berlin main street.

The development on Breitenbachplatz will be completed with individual buildings. The design contrast between the semicircle in the south-east and the more angular structure in the north-east is thus emphasised

In the south, at the foot of the Bierpinsel, the ramp structures are to give way to a small park. This also enhances the surroundings of the ‘Bierpinsel’ and helps to preserve the monument as a reminder of the past of the car-friendly city.

To the north, the block structure of the Rheingau neighbourhood beyond Mecklenburgische Strasse will be further developed. This area offers the greatest potential for careful redensification of the residential development. Heidelberger Platz, which today ekes out an existence as a little-noticed residual area, will be structurally redefined as a place to spend time.

At the crossing of the A100 city motorway, spaces are being created for striking building forms. In a park-like setting that complements the existing green corridor of the Volkspark, urban accents will replace the three demolished chimneys of the thermal power station in a rather open design.

The maze of entrances and exits at the former junction to the city motorway will be eliminated. A pedestrian and cycle-friendly bridge spans the A100 motorway and brings the residential areas on both sides of the noisy traffic axis closer together. A bicycle motorway connects the residential neighbourhoods in the south with the western city centre.

Beyond the city motorway on Hohenzollerndamm, a new residential development is being built that shields the existing allotment garden colony from the surrounding streets. With this new development, Hoffmann-von-Fallersleben-Platz will be urbanised.

In this way, 3,500 flats can be built on the areas that will be freed up directly by the demolition of the A104 motorway. The potential for a further 3,000 flats is growing on the neighbouring areas. The former road space is public property. This will create the basis for subsidised and affordable housing.

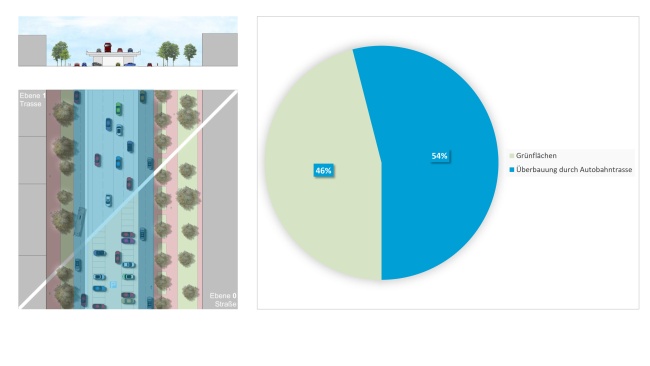

The now deserted areas under the now useless road viaduct will be transformed into a lively axis for urban mobility. Private transport, cyclists and local public transport share a reasonably dimensioned road space.

Level 2 - Visualisation for exemplary deepening

To deepen our understanding, we take the situation in front of the southern tunnel mouth at the ‘Schlange’ motorway superstructure as an example. Here the themes merge in one place:

- deconstruction of the former motorway,

- creation of new urban spaces,

- creation of new green spaces,

- dealing with the ‘Schlange’ architectural monument

The visualisation shows the view of the snake from Breitenbachplatz. The motorway ramps have been removed. Instead, a generous urban space opens up.

Traffic is lowered from the level of the elevated motorway to the normal street level. Intersections and meeting points are created. In order to utilise the existing road capacity, the carriageway bends to the west in front of the tunnel and leads into Dillenberger Strasse.

Traffic will move at the normal level of the western tunnel tube. This will not be a dark car tunnel, but a bright space that can also be crossed on foot or by bicycle. The parking spaces currently located there will be raised to the level of the former motorway. The eastern tunnel tube lends itself to being used as a public event space. This could become a public space protected from the weather, of which there are very few in the city.

A residential development is to be built in front of the tunnel mouth, framing a much narrower street space. This development also complements the blocks at this location that were once torn up to build the motorway. In this way, the large-scale ‘snake’, which is protected as a historical monument, will be juxtaposed with a city of people-friendly dimensions. The small-scale diversity of the architecture creates a new and surprising quality.

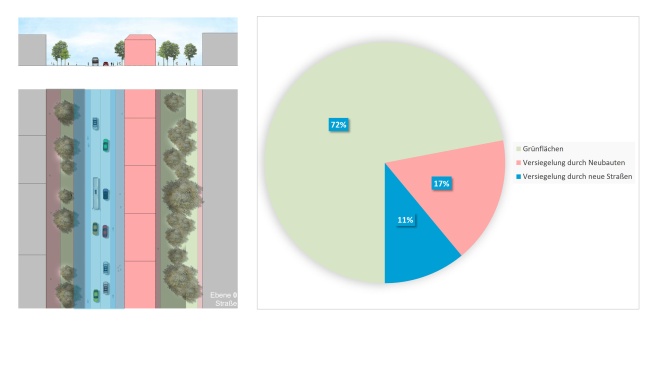

The inhospitable tarmac surfaces give way to a ribbon of green spaces. Once the carriageways have been broken up, large areas will be ‘unsealed’. Not only will plants grow there again, but rainwater can also seep away. As a result of this measure, approx. 35,000 m² of the 100,000 m² of carriageway will be reclaimed for the natural function of the soil. This is an important contribution to the ecological balance of the city.

Viewing direction of the big visualisation

Bird‘s eye view

of Breitenbachplatz from the south-west. The demolition of the motorway, which has destroyed the city, will reunite the square into one whole.

Rainwater infiltration

The dismantling of the motorway will transform around 35,000 square metres of sealed surface area into a natural area open to infiltration as part of the new residential development.

Suedwestkorso on the corner of Dillenburger Strasse, looking north. The dismantling of the ramp structures opens up the view into the street space.

View southwards from Breitenbachplatz into Schildhornstrasse. The noisy street becomes a pleasant residential address.

The listed Bierpinsel marks the new Promenadenplatz at the junction with Schlossstrasse.

Dillenburger Strasse: View from Breitenbachplatz to the north-west. New apartment blocks are being built in place of the elevated road.

View from Breitenbachplatz in the direction of Suedwestkorso. The new buildings recreate the historic edges of the square.

Always modern? What is modern?

The anticipation of the year 2070 is an enormous leap in time. We expect a world that has mastered the careful use of resources. The throwaway society will be a thing of the past. Progress in construction will be characterised by the careful use of existing buildings. How can we make what is there better? How can we use the spaces left behind by the large-scale structures of past industrialisation? How can we design architecture that will still be accepted by the citizens of the city many years from now? That is sustainability. The future does not belong to fashionable megaprojects for which the old is torn down only to fall out of fashion in ever shorter cycles. We must not consume this ‘grey energy’. The future belongs to an architecture of long life cycles.

Urban planning and transport technologies are closely interwoven. Noisy and smelly combustion engines will be a thing of the past. Autonomous vehicles will maximise safety. The available road space will be utilised efficiently. These same autonomous vehicles will serve local public transport. Waiting times will be reduced to a minimum. Fixed routes and timetables will become less important because fleets of vehicles will pick up and drop off individual passengers wherever they are by calling an app. With new communication functions, we will be able to work from anywhere in the world. This will make a large part of transport superfluous. Supply and disposal will be completely automated. For example, at night when the roads are clear. Traffic will no longer need the large areas that were once intended for the car-friendly city.

But it's not just technology that points to the future. Progress is also taking place in other areas. In the next few years, we will increase the efficiency of work, primarily through better organisation. Artificial intelligence will be able to take a lot of work off our hands. The separation of living and working areas will disappear. It was commuting between residential neighbourhoods and workplaces that once led to the desire for a car-friendly city. Living and working will increasingly merge. With the dissolution of the separation between the residential and working worlds, people will spend more time in one place again. As a result, the demands on the qualities of the city will grow. The superfluous traffic areas offer space for the creation of new qualities of stay.

The vision of the car-friendly city included an architecture that was called modern at the time. The buildings were to take on the smooth and streamlined forms of the speeding vehicles: Steel and glass, instead of stone and wood. Buildings were understood as machines. But smooth forms are not ‘functional’, they are short-lived and fragile. Reduced forms are also not economical, but lead to a fetish of expensive materials and immaculate surfaces. Both cause building costs to explode. Such architecture is therefore rarely sustainable.

The ‘snake’ is an example from this era. Just as the car-friendly city belongs to the past, this form of modernism has itself become history.

The car-friendly city took no account of the structures that had developed historically. They wanted something completely new. Back then, architects wanted a radical departure from history.

The architecture of the future once again takes people as its yardstick. This also includes memories. We always want to allow this collective memory to shine through in our architecture. This does not exclude foreigners, but makes them understandable. Such architecture is not exclusionary, but invites people to get to the bottom of history.

Modern architecture is diverse and rich in detail. It should have something to offer from any distance. Even when viewed from very close up, surprising qualities should still be recognisable. We do not believe in the smooth, low-detail, ostensibly functional and sometimes monotonous façades that have dominated recent decades. Modern architecture should arouse curiosity. It should whet the appetite for a rich future. That is modern.

The team

Patzschke Architekten are an international team based in Berlin. “Our architecture,” the group say, “points to the future and at the same time allows the beauty of the past to shine through. With subtle references to architectural history, our work blends into the cityscape. With an appreciation of timeless design, we stand for sustainable buildings and urban spaces.”

https://patzschke-architektur.de/